EM Crisis – More than Turkey & Argentina

News

|

Posted 04/09/2018

|

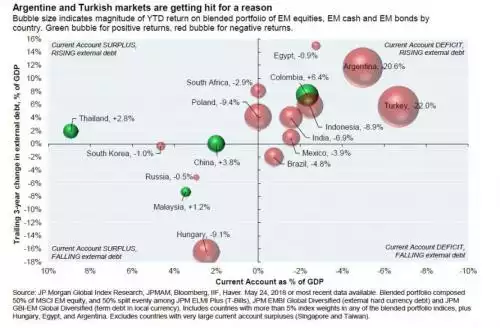

8573

Bloomberg’s Satyajit Das delivered an insightful piece yesterday titled “We May Be Facing a Textbook Emerging-Market Crisis” with the tag “Argentina and Turkey look like outliers but the rot could spread fast.”. One Emerging Market after another seems to be making headlines lately as their currencies implode. Whilst pressure has been building since 2013 during the ‘taper tantrum’ as the US Fed looked to ease it’s QE program, we then saw proper turmoil in 2015 when China made its sudden yuan devaluation (remember trying to get gold and silver then?!). Now it’s happening again with Turkey and Argentina taking most headlines but the pain being felt across many other Emerging Markets. How does this happen? Das spells out the classic recipe below and all the ingredients are on hand right now:

“The textbook recipe for an emerging-market crisis requires a large dose of debt and an associated domestic credit bubble, including misallocation of capital into uneconomic trophy projects or financial speculation. Then add: a weak banking sector, budget deficits, current-account gaps, substantial short-term foreign-currency debt and inadequate forex reserves. Season with narrowly based industrial structures, reliance on commodity exports, institutional weaknesses, corruption and poor political and economic leadership.

Based on these criteria, the number of emerging markets at risk extends well beyond Turkey and Argentina. Like Tolstoy’s families, each nation has different sources of unhappiness.”

As usual, a core issue is debt. And, as usual, a lot of this stems from the pumping of credit into the near broken system to prevent the GFC fully playing out.

“Total emerging-market borrowing increased from $21 trillion (or 145 percent of GDP) in 2007 to $63 trillion (210 percent of GDP) in 2017. Borrowings by non-financial corporations and households have jumped. Since 2007, the foreign-currency debt – in dollars, euros and yen – of these countries doubled to around $9 trillion. China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, South Africa, Mexico, Chile, Brazil and some Eastern European countries have foreign-currency debt between 20 percent and 50 percent of GDP.

In all, EM borrowers need to repay or refinance around $1.5 trillion in debt in 2019 and again in 2020. Many are not earning enough to meet these commitments.”

And there’s the crunch, debt needs to be repaid or refinanced to kick the can down the road. Many of these borrowers simply can’t do that. At a country level if you have the double whammy of running deficits domestically (spending more than received) PLUS current account deficits (value of goods and services imported exceeds that exported – ie money leaves shore) you can get to the point where you simply can’t repay your debt.

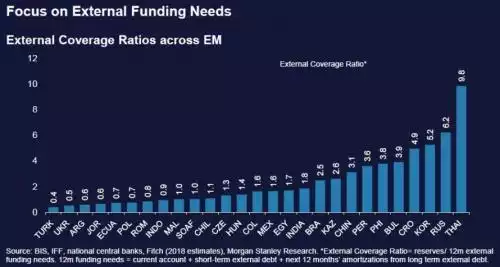

A measure of this is reserve coverage or “external coverage ratio” which is simply the country's reserves divided by its 12 month external funding needs, or even more simply how long that country has before it runs out of cash. As you can see from the chart below (Morgan Stanley), by no means are Turkey and Argentina the only ones with extremely thin ratios:

As Das says:

“Turkey and Argentina score 0.4 and 0.6 respectively, meaning they can’t cover their needs without new borrowings. Pakistan, Ecuador, Poland, Indonesia, Malaysia and South Africa have reserve coverage of less than 1.”

Importantly too, he warns we shouldn’t be relaxed about those EM’s with higher ratios as debt expiries loom, ‘available’ foreign reserves may not be that ‘available’, and, well, governments don’t always tell the truth. To wit:

“Even where reserve coverage appears adequate, caution is warranted. Long-term debt becomes short term with the passage of time or an acceleration event. Forex holdings may not be readily accessible. Much of China’s $3 trillion of reserves is committed to the Belt and Road infrastructure initiative. The ability to turn U.S. Treasury bonds and other foreign assets into cash is limited by liquidity, price and currency effects. Reserve positions are notoriously opaque: In 1997, the Bank of Thailand was found to have grossly overstated available currency holdings.”

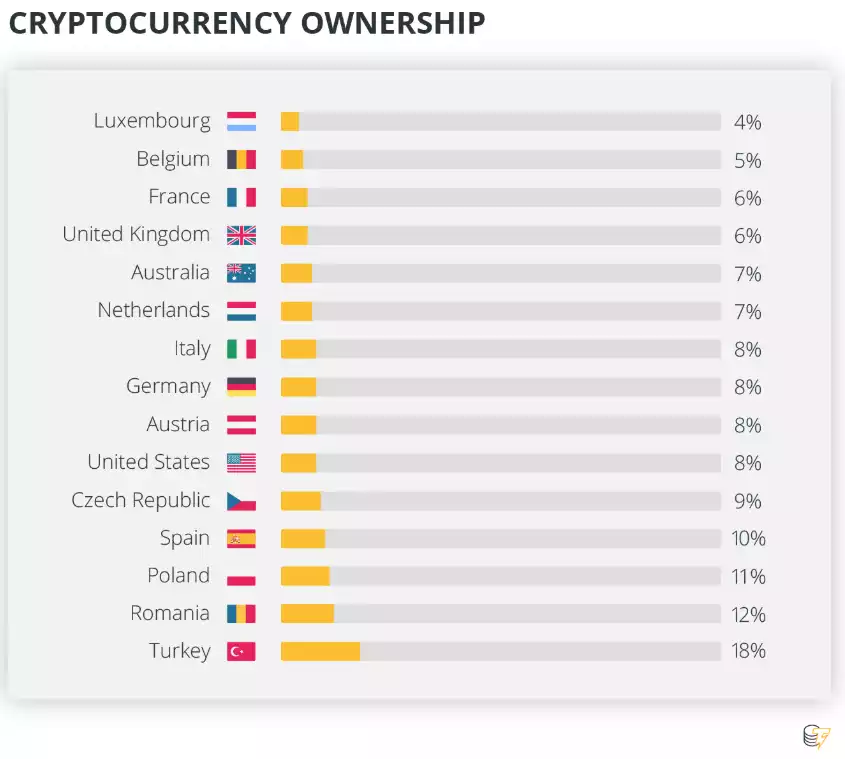

Whilst a flight to gold in such times is a well-worn and profitable move for anyone experiencing a devaluation of their currency, the chart below shows cryptocurrencies are also being used for the same purpose by the residents of Turkey in particular:

Let us leave you with Das’s final warning:

“Turkey and Argentina may be special cases. But given the fundamental problems, other emerging markets are likely to come under pressure. As Herbert Stein's 1976 law states: “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.””