Cash Ban Senate Submission

News

|

Posted 05/11/2019

|

39863

In just 10 days submissions close for the Senate Inquiry in to the cash ban legislation bill. We have written previously on this cash ban here. Commentator and vocal opponent Matt Barrie has penned an excellent submission that we felt compelled to share.

Submission to the Australian Senate Inquiry into Banning Cash

2nd November 2019

By electronic mail to: [email protected]

The Senate Standing Committee on Economics

PO Box 6100

Parliament House

Canberra ACT 2600

Dear Senators,

It is clear that the move to ban cash is primarily driven to prepare the country for a zero or negative interest rate environment.

Severe recessions historically require central banks to cut the policy rate by 3–6%. With monetary policy since the GFC distorting the global financial system only a small number of central banks in OECD nations have the firepower left to do this.

Current policy rates of major central banks

Source: Global-rates.com

To combat this, the International Monetary Fund has redefined the limit of monetary policy from a “zero lower bound” to an “effective lower bound”, a euphemism for negative interest rates.

In Cashing In: How to Make Negative Interest Rates Work (which I strongly suggest everyone in Australian Parliament reads) the IMF openly discusses a central bank cutting the policy rate from 2% to negative 4% to combat a severe recession.

It goes on to say:

“When cash is available, however, cutting rates significantly into negative territory becomes impossible.”

“Cash has the same purchasing power as bank deposits, but at zero nominal interest. Moreover, it can be obtained in unlimited quantities in exchange for bank money. Therefore, instead of paying negative interest, one can simply hold cash at zero interest. Cash is a free option on zero interest, and acts as an interest rate floor.”

“Because of this floor, central banks have resorted to unconventional monetary policy measures. The euro area, Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden, and other economies have allowed interest rates to go slightly below zero, which has been possible because taking out cash in large quantities is inconvenient and costly (for example, storage and insurance fees).

These policies have helped boost demand, but they cannot fully make up for lost policy space when interest rates are very low.”

Make no mistake, the primary motive behind Australia’s proposal to ban cash transactions above $10,000 is to prepare the country for a negative interest rate environment.

This is a world where Australians could wake up to find that their local bank account takes 4% of their savings each year, because theorists working for central banks believe that this is a great way to grow an economy- the theory being that consumption (and by virtue of that the economy) will grow because otherwise the bank will take your hard earned savings.

I do not know how the financial system can function in that environment. The business of a bank is to borrow money from savers, who are effectively unsecured creditors, and lend it to people who can find a productive purpose for it.

With negative interest rates, there is no rational reason to deposit money in a bank unless cash is banned.

We should not let Australia go down the path of negative interest rates as it will make our financial system less stable. The Australian economy has been warped by government policy to such a state that there are very few entities to lend money to other than a consumer to purchase residential housing in a stratospherically overpriced residential housing market. The Big Four issue over 80% of residential mortgages in Australia, and are more exposed as a percentage of loans than any other banks in the world, over double that of the U.S. and triple that of the U.K., and remarkably quadruple that of Hong Kong, which is the least affordable place in the world for real estate. Over 60% of the Australian banks’ loan books are residential mortgages.

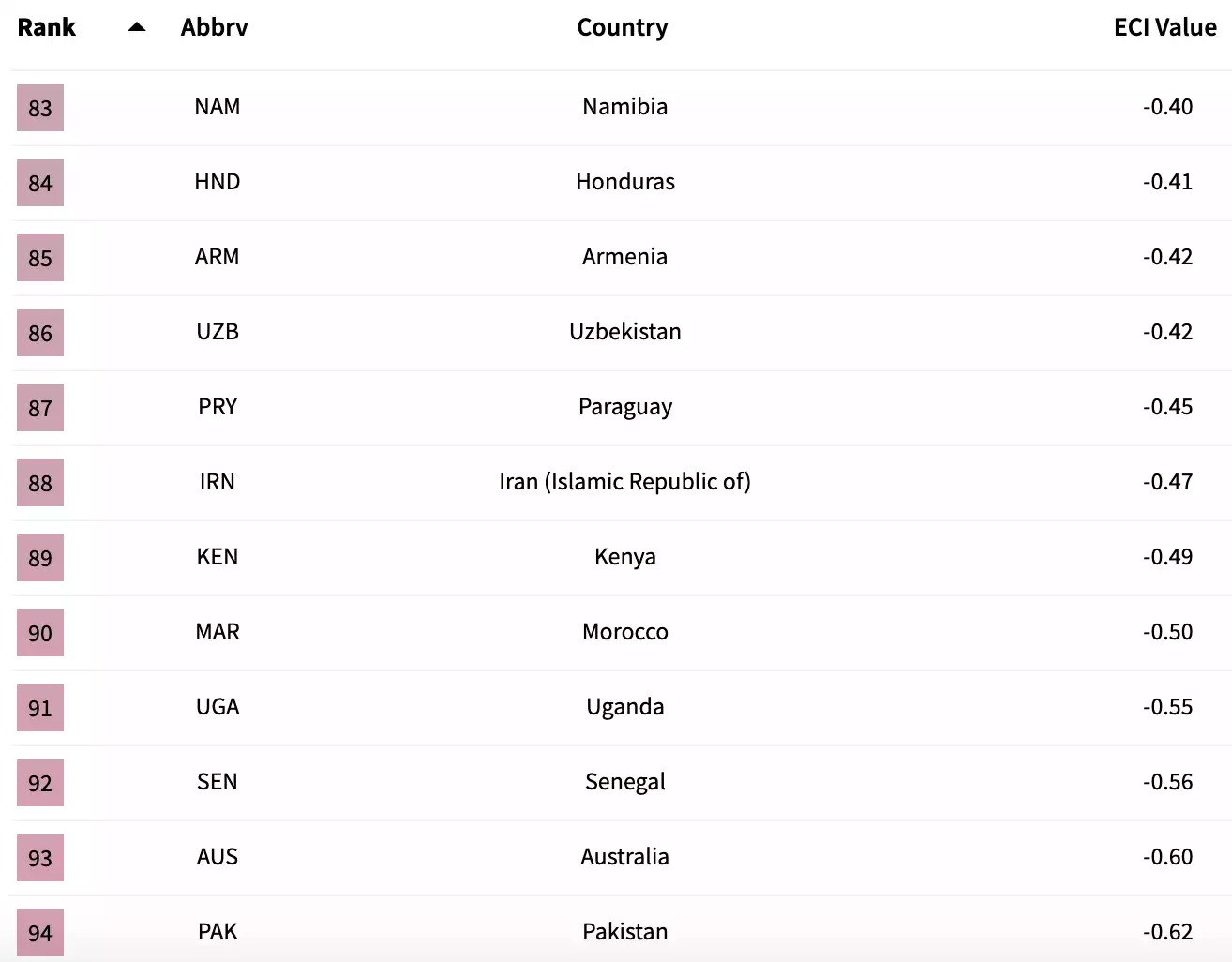

It’s at such a high level because we have let the sophisticated industrial side of our economy fall apart- Prime Minister Paul Keating warned us of this risk in 1986. Australia has fallen to 93rd position in the Harvard Economy Complexity Index, which is a measure of economic diversity- how many different products a country can produce- and economic ubiquity- how many countries are able to make those products.

Australia ranks 93rd in the Harvard Economic Complexity Index

Source: Harvard

I believe that Australian banks are in a precarious position with such a high exposure to residential mortgages. The Australian banks were effectively insolvent in 2008 when the GFC resulted in their foreign funding lines being cut off until the government stepped in to provide liquidity and deposit guarantees. I think that we will face a crisis of this magnitude, or worse, in the near future and that at least one of the Australian banks will need to be rescued with some running portfolios of mortgages 700–900% of their market capitalisation.

If there isn’t enough instability already, some of the pillars of modern finance literally break with negative interest rates. You cannot price an option with negative interest rates using the Black-Scholes equation. The risk-free rate, or rate of return of an investment with no risk of loss, often derived from the long dated government issued bonds, should not even be anywhere near zero percent. Over 50% of European government bonds have a negative yield. In October a $1 billion Australian Treasury note tender was undersubscribed for the first time ever because the yield wasn’t attractive enough. Banning cash is taking Australia a step down the path of financial insanity.

The cash ban is unnecessary. Physical cash in circulation is only 4% of GDP in Australia according to the IMF and declining.

Percent of cash in circulation in selected countries.

Source: IMF

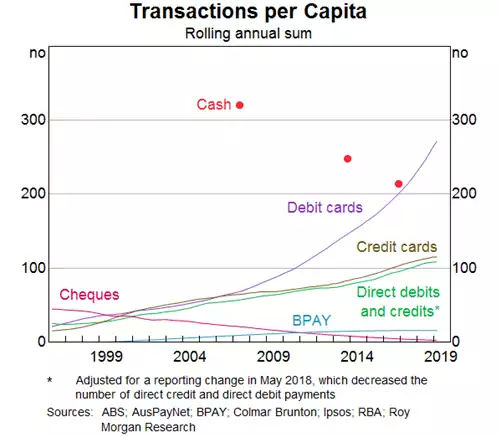

Transactions per Capita, Australia (1996 to 2019)

Source: itNews and above sources

The cash ban is also discriminatory to people with low incomes who have less access to appropriate low cost, fair and safe financial products and services from mainstream providers.

While the report is fifteen years old, a 2004 Roy Morgan survey found that 0.8% of the Australian adult population owned no financial products and 6% owned only a transaction banking product.

For this reason, New Jersey, Philadelphia and San Francisco have banned cashless stores. New York is considering such legislation.

Poor access to financial products can also apply to individual small businesses, NFPs and other community enterprise organisations. The Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry is against the ban and says there is “no hard evidence” showing large value cash transactions were a broad problem or that cash itself is the cause of black market activity.”This policy will do little to nothing to inhibit black market or illegal activity” said the ACCI in a 2018 submission to Treasury.

Cash is good for commerce- it avoids unnecessary bank charges and transaction fees. Moving money around and in and out of the banking system can be expensive. ATMs can charge up to $2.50 to withdraw cash. That is a tax of 12.5% on a withdrawal of $20. Vendors give discounts for cash, as it is a preferred form of liquidity.

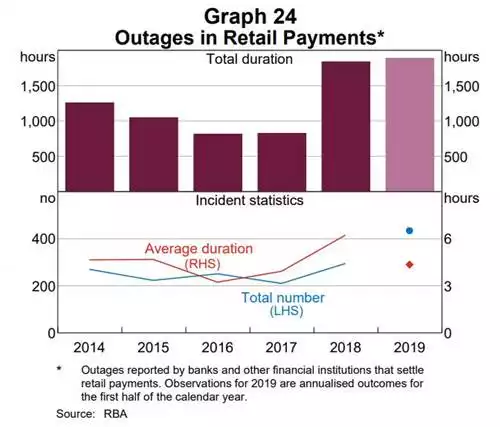

The cash ban should not be passed because people will not be able to transact if there are technology outages. There were 295 such failures in 2018, and the frequency and duration of such outages are getting worse. There were 210 failures in 2017 and 251 in 2016.

In the past year, such outages have soared 40%. The total duration of retail payments outages in hours as reported to the RBA hit its worst annual level in five years in 2018 with 1838 hours of incidents compared to 824 hours in 2017, and 811 hours in 2016.

The average duration of an outage was up significantly in 2018 to 6.2 hours in 2018, versus to 3.9 hours in 2017 and 3.2 hours in 2016.

Outages reported in retail payments in Australia 2014–19

Source: RBA, itNews

The full extent of outages is not known and has prompted the Payment Systems Board to force financial institutions to report outages in future.

Climate change forecasts an increasing frequency of natural disasters. California has just experienced wildfires and power outages to such an extent the ABC posits “California’s new normal?”. PG&E power outages have affected 2.5 million people with some being without power for over a week.

The cash ban would make it a crime to transact in such a scenario- emergencies are precisely the time when it might be critical to purchase something. To deal with this, the proposed legislation contemplates it not being illegal to transact over $10,000 when there is a natural disaster such as a fire or a power outage. Of course, because less physical cash will be in the system if this ban goes through, the ability to find and withdraw such cash in the case of an emergency will be harder. The exemption- you’re a criminal possibly facing a $25,000 fine or two year’s jail for transacting, but not unless there’s an earthquake or the telephone network goes out- illustrates the sheer absurdity of the proposal.

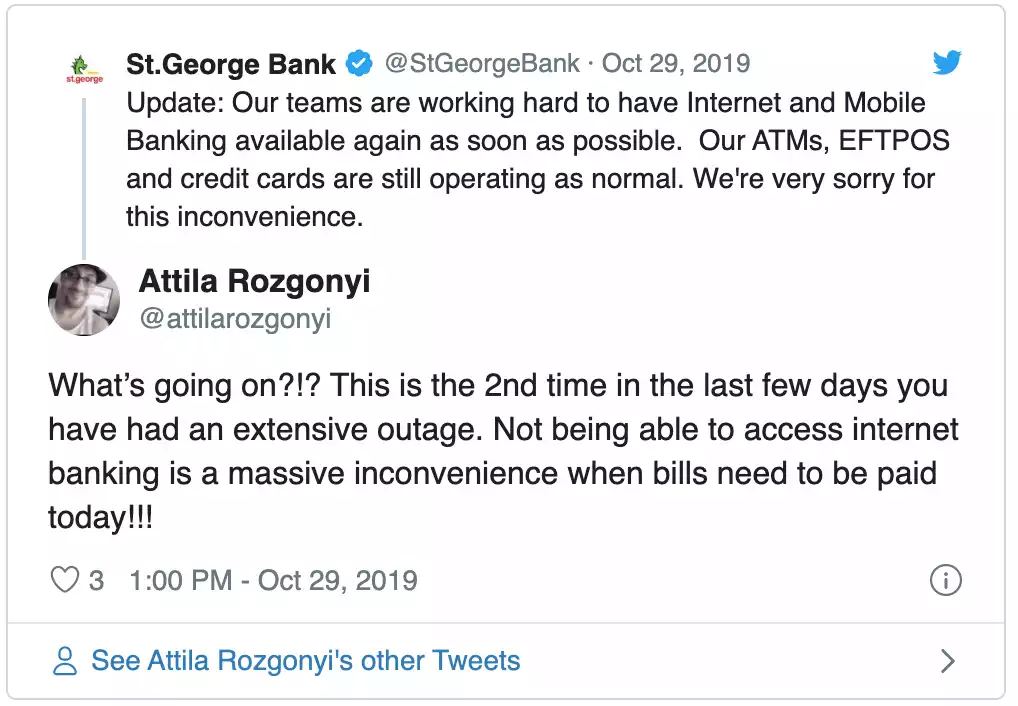

In the last number of weeks, multiple Australian banks had technology failures. On the 17th October 2019, the Commonwealth Bank had an outage “leaving millions of Australians without access to their accounts and many other non-CBA customers without expected payments”.

St George Bank, had two outages this week, on the 26th and 29th of October 2019. The Bank of Melbourne and Bank of South Australia were also affected by these outages.

Customer not happy over the St. George Bank outage

Source: Twitter

Finally, the fiat issued money only works due to the collective faith that they will ultimately be able to trade it for real assets, products and services. To instil that collective faith, money used to be convertible into a fixed amount of gold or silver, particularly good stores of value that are hard to counterfeit. In one of the greatest tricks to ever be pulled on the public, governments figured out that by moving off a gold standard that restraints could be removed on spending- all in the guise of “stimulating the economy”. Of course, someone has to lose, and people who hold this money ie. savers are the ones to lose. Since fiat went off the gold standard, the value of such relative to real assets has collapsed. This fall in the purchasing value of money is the very definition of inflation.

The Old Testament states that in 600 BC, during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar, one ounce of gold was worth 350 loaves of bread (loaves were just under one kilo size back then). Today, the 2nd of November 2019, one ounce of gold is worth AU$2,191.66 and the price of bread is about 50 cents per 100 grams. This makes one ounce of gold worth about 438 loaves of bread. There’s plenty of other examples of gold and silver holding their purchasing power fairly static versus other real assets over any time period that we’ve used money. Over two and a half thousand years, they have performed tremendously well for savers.

The Australian dollar, on the other hand, hasn’t. The value of the Australian dollar relative to gold, or a proxy for real assets, has fallen around 75% in the last fifteen years, losing around 9% of its value per year on average.

The change in gold price relative to various fiat currencies (2004–2019)

Source: Goldprice.org

The change in the price of gold relative to the Australian dollar (2005–2019)

Source: Goldprice.org

There has already been a poor argument for saving in Australian dollars instead of converting into a real asset that is a proper store of value, such as buying a house, which in this country are now some of the most unaffordable in the world and Australian households the second most indebted in the world and with the second highest average principal and interest repayments on that debt. Why would you put your money in the bank, when you are guaranteed to get less back later? Unquestionably this will erode the deposit base.

As speculated by the IMF, anything that is be a political problem for the Reserve Bank now also becomes a customer relationship problem for our Australian banks.

The $10,000 cash ban is the first step along the path to banning all cash, which will allow government significantly greater overreach in the ability to force the public to stop saving and spend via unconventional monetary policy. This, by design, is to drive inflation and will devalue the value of money relative to real assets even further.

This will further damage the collective faith that the money issued by the Reserve Bank of Australia is sound and that people should hold it.

The next steps will otherwise involve banning cash outright, banning gold (which the US did under Executive Order 6102 in 1933) [we beg to differ as outlined in this interview], cryptocurrencies and many other liquid assets, or stores of value. Of course, this will all be done under the auspices of stopping the black economy.

Australians have already had to put up with modifications to “bail-in” laws via the Financial Sector Legislation Amendment (Crisis Resolution Powers And Other Measures) Bill 2017, which was passed on Valentine’s Day 2018 with just 7 senators present. [we wrote about this here and is a must read if you haven’t] This cash ban is designed to keep more money “in the system” so that in a crisis the deposits of savers can be used to bail a troubled bank out, just like we saw in Cyprus in 2012–3. This now allows APRA to confiscate the cash savings of SMSFs, and while in New Zealand similar laws allow the confiscation of depositors’ funds, the Australian law cleverly doesn’t specifically exclude that.

Simply, via the cash ban you’re being forced to keep more money in banks, who can then use that money to bail themselves out if they have lent recklessly, which I think our Australian banks have with their exposure to residential property and the extremely high default correlation that loan book poses.

The line needs to be drawn with stopping this madness or the next senate inquiry will likely be over one of the following:

Banning cash outright.

Eliminating large denomination bills (already being floated- even though the $100 note issued in 1984 had the buying power of almost $300 today from inflation or six times the value if you consider relative to the price of gold- just wait another 35 years and it will likely have the buying power of less than $30 of today’s money).

Dividing the monetary base into two separate local currencies — cash and electronic money (e-money). E-money would be issued only electronically and would pay the policy rate of interest, and cash would have an exchange rate — the conversion rate — against e-money. Either “the clean approach” which is an electronic money system that takes paper currency off par, and (b) “the rental fee approach” which keeps paper currency at par.

Putting an expiry date on bank notes, for example when issued by the ATM.

Requiring that stamps be purchased and affixed to paper currency periodically — effectively allowing the government to tax paper currency.

A variable consumption tax, such GST, depending on whether you purchases with paper or electronic money.

A serial-number-lottery plan in which each year the central bank would pick a number between zero and 9 out of a hat, and all bills with a serial number ending in that number would no longer be legal tender.

All of these proposals, and more, are discussed in the IMF working paper Enabling Deep Negative Rates to Fight Recessions: A Guide which was published in April of this year.

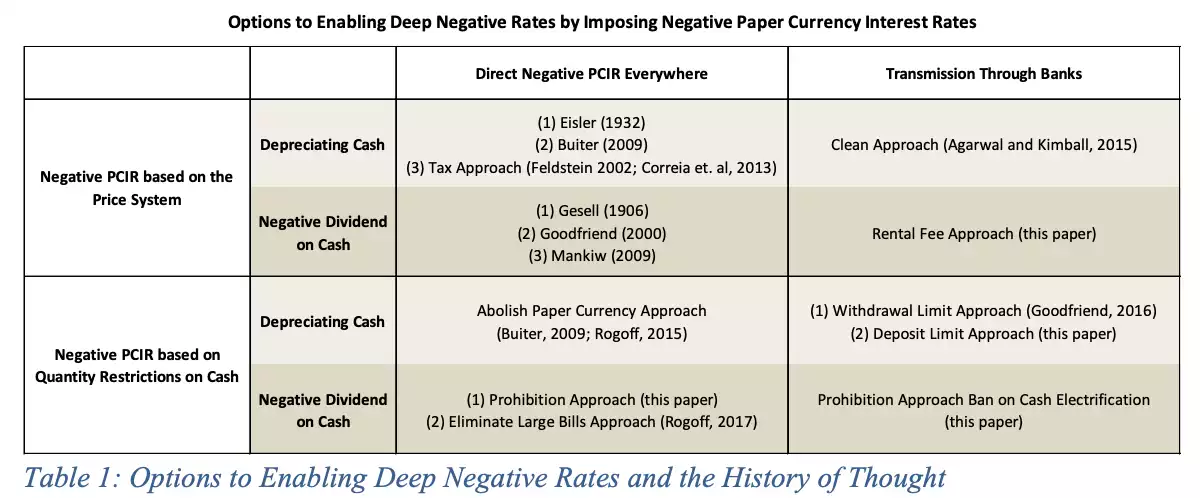

Options to Enabling Deep Negative Rates and History of Thought

Source: Enabling Deep Negative Rates to Fight Recessions: A Guide (IMF)

Even with these proposals the IMF found “the best approaches for enabling deep negative rates (i.e. both at a minimum distance from the current monetary framework and the least costly politically) are those that both rely on banks for transmission and do not impose quantity restrictions on cash”. Restrictions on cash, for example, that this cash ban is proposing.

Cash is legal tender. It is written on the physical note. While our central bank can’t always spell “responsibility” on the cash it issues correctly, the government has the responsibility of making money sound.

An Australian $50 note

Source: The Reserve Bank of Australia

The cash ban creates an environment where using certain forms of government issued money would make you a criminal when making transactions that would otherwise be perfectly legal.

I can only imagine that this will lead to transactions being structured to be worth just under the $10,000 limit. Does this subsequently make those parties criminals for transacting $9999 in cash? $9900? Where does this end up? I haven’t even touched on civil liberties and whether the general public should be forced to use a bank.

Based on the past performance of the Australian dollar since inception, in 10 years from now the $10,000 threshold will have the buying power of a little over $8000 and in 50 years less than $770 in today’s money.

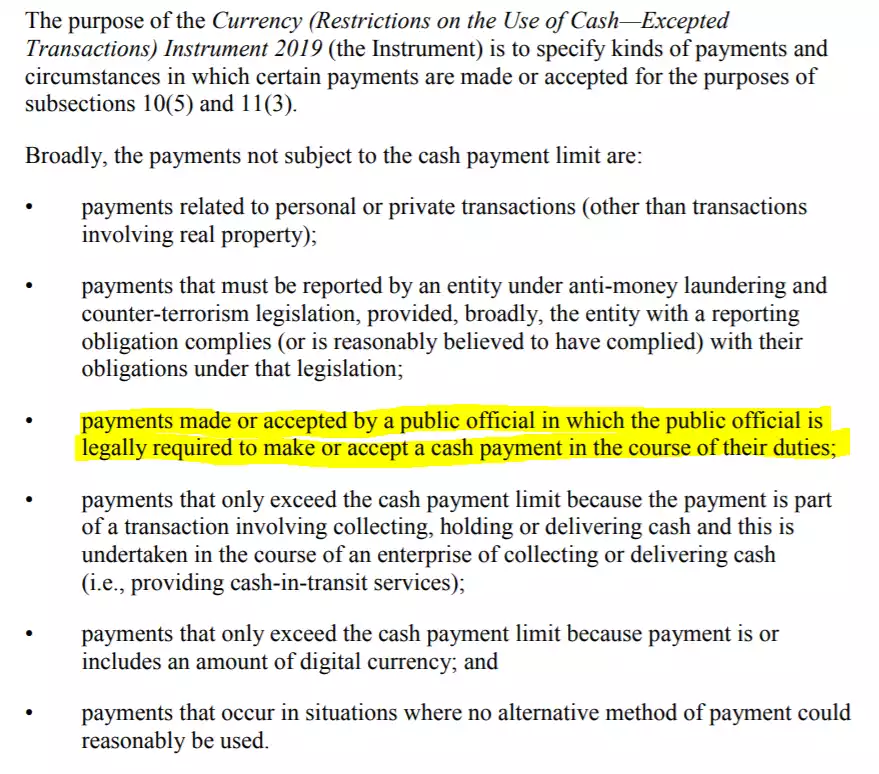

Finally, in reading the actual legislation, I noticed an exemption for public officials where they are required to make or accept a cash payment. Under what circumstances is a government official required to make or receive more than a $10,000 cash payment?

Exposure Draft Explanatory Materials

Source: Treasury

Cash is legal tender, let’s keep it legal tender, just like it says on the note.

You too can act and make your own submission before the deadline to the address above.