Zero Gold Discoveries: What a Historic First Means for Supply and for You

News

|

Posted 12/02/2026

|

2589

For the first time in recorded history, the global mining industry has gone two consecutive years without a single major gold discovery. The implications for supply, price and the broader mining cycle are significant.

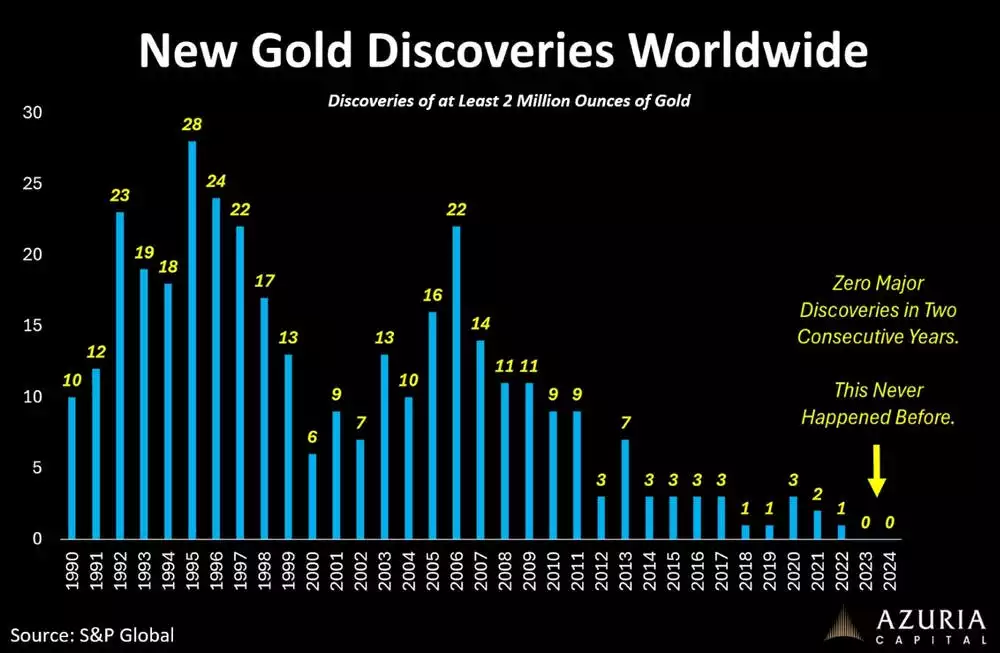

There is a chart doing the rounds on financial social media that warrants more than a passing glance. Shared by macro strategist Tavi Costa of Azuria Capital, it draws on S&P Global data to show the number of major gold discoveries, defined as deposits of at least two million ounces, made worldwide each year since 1990. The trajectory is unmistakable and the endpoint is historic.

New Gold Discoveries Worldwide, 1990–2024. Discoveries of at least 2 million ounces. Source: S&P Global, via Azuria Capital / Tavi Costa (@TaviCosta).

In 2023 and again in 2024, the global mining industry recorded zero major gold discoveries. Not a slowdown. Not a lean year. Zero. This has never occurred before in the modern era of gold exploration data.

As Costa noted in his commentary, this trend is not unique to gold. Major discoveries across most metals have fallen into the single digits, with no meaningful projects in the pipeline capable of materially altering the global supply curve. In his view, this is the real barometer of where we are in the mining cycle and we are still early.

The Numbers Tell a Clear Story

Looking at the chart, the peak years for major gold discoveries were the mid-1990s, when 20 to 28 significant deposits were being found annually. The 2000s saw a meaningful decline but still produced occasional strong years, including 22 discoveries in 2006. Since 2010, the numbers have largely been in single digits. Now, for the first time ever, we have two consecutive years of nothing.

S&P Global’s analysis reinforces what the chart illustrates. Between 1990 and 2024, 353 deposits were identified globally, containing around three billion ounces of gold. The recent trend is more concerning. Since 2020, only a handful of significant discoveries have been recorded, and the average size of those deposits has shrunk materially compared with previous decades. None of the discoveries made in the past ten years rank among the thirty largest gold finds ever recorded.

19%

Share of 2024 exploration budgets allocated to grassroots, or new frontier, projects, down from 50% in the mid-1990s

Why Has Discovery Dried Up?

The answer is not simply that mining companies stopped looking. Global gold exploration spending reached US$7 billion in 2022. However, it fell 15% in 2023 and a further 7% in 2024, ending an uptrend that had been building since 2017. Tighter financing conditions for junior explorers, the companies that historically undertake the highest-risk frontier work, have played a major role.

Spending levels tell only part of the story. The more structural issue is where that capital is being directed. In the mid-1990s, roughly half of all exploration budgets were allocated to grassroots projects, drilling in new and untested areas. By 2024, that figure had dropped to just 19%. The industry has become markedly more risk-averse, preferring to extend the life of known deposits rather than venture into new terrain.

More than half of all initial resource announcements between 2020 and 2024 came from existing projects, not new ground. Mining companies are effectively extracting more from what they already control instead of focusing on what comes next. As S&P Global’s Paul Manalo observed, a decade-long focus on older and known deposits limits the probability of major discoveries in early-stage prospects.

The Supply Squeeze Is Real

Global mine production has essentially plateaued. According to the World Gold Council, mined output was virtually unchanged in 2023 and 2024, hovering between 3,645 and 3,672 tonnes annually. While 2025 may edge slightly higher, projections from Metals Focus indicate that production is likely to plateau gradually over the next few years rather than expand meaningfully.

The reason is straightforward. You cannot produce gold from deposits that have not been found. The pipeline of new projects capable of replacing depleting mines is thin. The US Geological Survey estimates that roughly 54,000 to 57,000 tonnes of identified economic gold reserves remain globally. At current mining rates of around 3,300 to 3,600 tonnes per year, those known reserves could be substantially drawn down within two decades, assuming no major new discoveries.

“Gold miners have not been able to increase their revenues while the metal price remains near all-time highs. In short, this is mainly a function of supply issues, a key part of the investment case for gold. Mining companies have had difficulties finding new discoveries while the quality of their existing reserves continues to deteriorate, with average grades steadily declining over the last decade.”

Tavi Costa, Azuria Capital

This matters because it is not a problem that higher gold prices alone can resolve. Even if exploration budgets increase, and there are signs they may as gold stabilises well above US$3,000 per ounce, there is typically a lag of six to ten years between discovery and first production. A deposit found today, if one were identified, would not produce its first ounce until the early to mid-2030s at the earliest.

Demand Is Moving the Other Way

While new supply stagnates, demand has surged across multiple fronts. Central banks bought more than 1,000 tonnes of gold in each of 2022, 2023 and 2024, roughly double the annual average of the prior decade. Poland, China, India, Turkey and Kazakhstan have been among the most active accumulators. In 2025, central bank purchases remained substantial at an estimated 863 tonnes, still well above historical norms.

The World Gold Council reported that total gold demand in 2025 exceeded 5,000 tonnes for the first time. Combined with 53 new all-time price highs during the year, the gold market saw an unprecedented annual transaction value of US$555 billion.

This is not speculative excess. Central banks are buying gold for structural reasons, including reserve diversification, reduced reliance on the US dollar and a hedge against geopolitical risk. J.P. Morgan projects strong investor and central bank demand averaging around 585 tonnes per quarter through 2026 and sees potential for gold to approach US$5,000 per ounce by late this year.

What This Means for Australia

Australia occupies a unique position within this global dynamic. As the world’s third-largest gold producer, with estimated in-ground reserves of 12,000 tonnes, the largest of any country, and output expected to rise from 293 tonnes in 2024–25 to around 369 tonnes by 2026–27, Australia’s gold sector is a direct beneficiary of the supply-demand imbalance playing out globally.

Gold is on track to become Australia’s second-largest export earner after iron ore. Export earnings rose 42% to $47 billion in 2024–25 and are forecast to grow a further 28% to $60 billion in 2025–26. Gold exploration spending in Australia has also increased materially and now accounts for roughly a third of total mining exploration expenditure nationally.

However, Australia is not immune to the discovery drought. Australian Bureau of Statistics data reflects the same global trend of declining discovery rates. While higher prices are reviving investment in brownfield expansions and previously uneconomic projects, the structural challenge remains clear: much of the easily accessible gold has already been found.

Why This Matters for Gold Investors

For anyone holding or considering physical gold, the supply picture is arguably one of the most underappreciated drivers of the current market. Media coverage often focuses on geopolitics, interest rates and central bank buying, all valid factors. Yet the inability of the mining industry to replace what it extracts each year is the deeper structural underpinning of the long-term price case.

Costa’s argument, that we remain in the early stages of a major mining cycle, rests on this point. The last two secular bull markets in gold coincided with multi-year declines in metal production. If mine supply does plateau or decline from here, as multiple forecasters suggest is likely within the next few years, the supply-demand imbalance will only intensify.

Gold is almost infinitely recyclable. It does not get used up in the way oil or copper does. Recycling currently contributes around 1,400 tonnes annually to total supply. However, recycling alone cannot offset a structurally declining discovery pipeline, particularly as demand from central banks, institutional investors and retail buyers continues to expand.

The chart shared by Tavi Costa is simple, but the message is significant. The mining industry is finding less gold than it is extracting. New deposits are smaller and lower grade than in previous decades. Capital that might otherwise fund major new exploration is largely being directed toward extending the life of existing mines.

For investors who understand supply dynamics, this is a development worth close attention. The gold you can hold in your hand today came from deposits discovered years, often decades, ago. The gold that should be discovered in the years ahead? At present, the pipeline is effectively empty.

At Ainslie Bullion, we have been helping Australians navigate precious metals markets since 1974. If you would like to discuss how physical gold may fit within your broader investment strategy, our team is here to assist.

Sources

S&P Global Market Intelligence; World Gold Council, Gold Demand Trends Full Year 2025; Metals Focus; US Geological Survey; Australian Department of Industry, Science and Resources; Minerals Council of Australia; J.P. Morgan Global Commodities Strategy. Chart: S&P Global data via Azuria Capital / Tavi Costa (@TaviCosta on X).

Disclaimer: This article is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute financial advice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Gold prices can and do fluctuate. Investors should consider their own circumstances and seek independent financial advice before making investment decisions. Ainslie Bullion is a bullion dealer, not a licensed financial adviser.