What is Moral Hazard?

News

|

Posted 02/12/2022

|

12781

“Show me the incentives, and I’ll show you the outcome.”

- Charlie Munger, Berkshire Hathaway

‘Moral Hazard’ is a core concept in Austrian economics which describes how individuals and businesses can receive misleading economic incentives.

The classic case of moral hazard came in 2009 when banks on the brink of collapse were bailed out with public funds. Leverage led to outsized profits in the good times, but losses were socialised in the crash. By increasing their risk profile, bank executives were able to pay themselves generous bonuses and stock options. No bankers went to jail, barely any of them lost their jobs, and the circus rolled on. The message this sent to banks in the aftermath… risk it all, and that’s exactly what they have done since 2009 as the global derivatives market has continued to balloon, making the entire system more and more fragile and susceptible to systemic collapse.

Without the real threat of bankruptcy and executives going to jail, there is little reason to save for a rainy day. Another example was the bailout of the airlines in the wake of the 2020 pandemic scare. On 27 March 2020, the US Congress approved $25 billion in taxpayers dollars to prop up 10 major passenger airlines. In the 10 years prior to the pandemic however, the top five US Airlines spent an average of 96% of their free cash flow on share buy backs to pump their stock price and the executives bonuses as a result. If directors and executives were to be held responsible for the fallout in a crisis, then they might have kept back a little more of that free-cash flow. Perhaps they knew that Uncle Sam would always have their back if things ever turned out badly.

As a simplistic example, a cashier in a supermarket is skimming a small amount of petty cash each week. It seems like a great way of raising some extra cash for as long as it lasts. However, when the manager finds out, they are required to repay the stolen money and lose their job. They are now in a much worse financial position than they started, and the meager gains weren’t worth risking the whole enterprise.

Imagine a world though, where rather than the manager reacting like that, the staff member claimed that they had a mental illness, and as a result, the manager gives them a promotion. They have kept all the winnings, and even come out ahead. What has the employee learnt, that stealing and lying have no real negative consequences, so long as the truth is never found out.

Everytime banks such as Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) risk the farm and then are bailed out by governments or Central Banks, it rewards excessively “risky business”. In traditional capitalism where free and open markets are the norm, bankruptcy is a healthy part of a functioning free market.

Speaking in the Hidden Secrets of Money Episode 2, Mike Maloney explains how the incentives for politicians are always to spend on public works and welfare, in the process diluting the value of the currency and weakening society as a whole. In the short term, they retain popularity and power, in the long-term… well, that’s someone else’s problem once they are out of office. The skill of politics is to kick the can down the road, and just hope that you aren’t the one holding the bag when the road ends (as all roads must) or the ‘chickens come home to roost’.

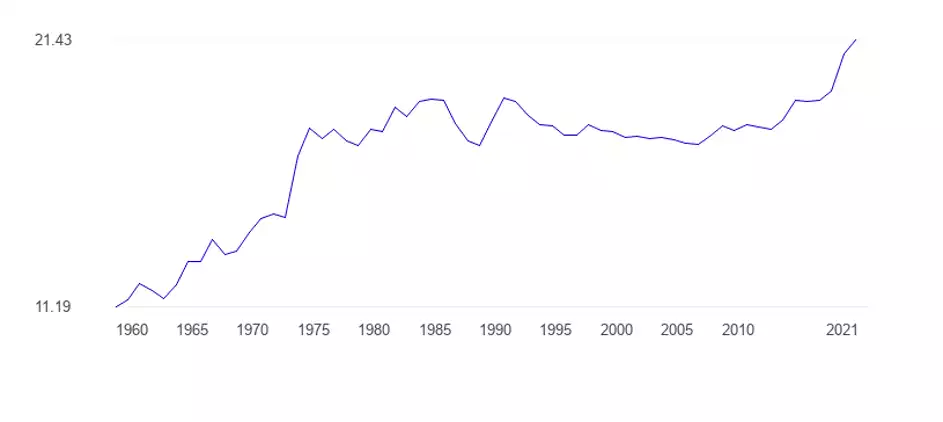

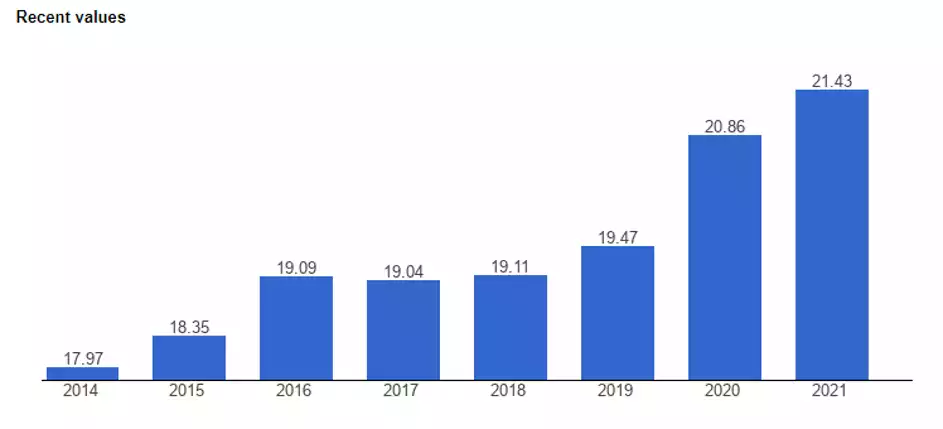

Over time, individuals and businesses become more and more dependent on ever increasing government stimulus just to keep going. Government starts as a very small percentage of GDP, and over time it comes to define the economy.

In the early 1960s, government spending was only 11% of GDP, but this has stretched out to more than 21% in 2021. The last five years have certainly seen a quickening.

These figures may not tell the whole story however, as the 2020-21 lockdowns saw vast areas of the Australian economy shut down completely, surely government spending would have been significantly higher as a percentage during that period.

This additional government largesse is only possible through currency devaluation. The government itself doesn’t create additional goods and services, it taxes businesses generating profit, then taxes their employees on their income, and then taxes those employees when they spend their money at, you guessed it, businesses that provide goods and services.

So why does moral hazard matter? In the words of Wall Street legend Charlie Munger of Berkshire Hathaway, “show me the incentives and I’ll show you the outcome”. Central banks, the governments that enable them, and the politicians seeking reelection in the near future, all have incentives to devalue currency and reduce the purchasing power of everyday savers. There is no incentive for them to institute long term reforms and take the pain in the short term for the benefit of the system as a whole.

We often talk about ‘kicking the can down the road’. The only problem is, we may be reaching the end of the road. One scenario is that deposits in banks are bailed in, or their value is severely reduced when transitioning from the old system to the new system - whatever that new monetary regime may be. When banks looked like going under in the GFC, the Australian Government gave a guarantee, but since then, the bail-in laws have ensured that in the next liquidity crisis, the final victim will be the unsecured creditor i.e YOU… the bank depositor with a savings account.

For more information, please see one of our most popular articles of all time, (more than 100,000 views: Bank Bail-ins in Australia: Why your cash isn’t safe (19/7/2019).