This Commercial Real Estate Crisis Could Bring Down the Regional Banks

News

|

Posted 22/11/2023

|

2371

As we have discussed throughout the year, the banking crisis continues to worsen, however the final nail in the coffin could come from a somewhat unexpected source, the CRE sector.

Over a month ago, data released by the Federal Reserve indicated ongoing challenges in the banking sector, signalling a persistent banking crisis. The current situation has intensified, with regional banks struggling to address issues in their balance sheets. In addition to these challenges, they now face a looming threat in the potential collapse of the Commercial Real Estate (CRE) sector, which could pose significant problems for smaller banks, even if they manage to control deposit outflows.

This unfolding scenario draws uncomfortable parallels to the previous real estate crisis during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008, primarily impacting residential properties. The mortgage meltdown during that period resulted from numerous Americans facing difficulties in meeting mortgage payments, causing financial derivatives linked to these payments to plummet.

The aftermath saw a sharp decline in home prices as options for cash-out refinancing disappeared, cutting off a significant source of cash flow and leading to a decline in consumer spending. Subprime loans, based on the assumption of continual increases in home values, turned into underwater nightmares.

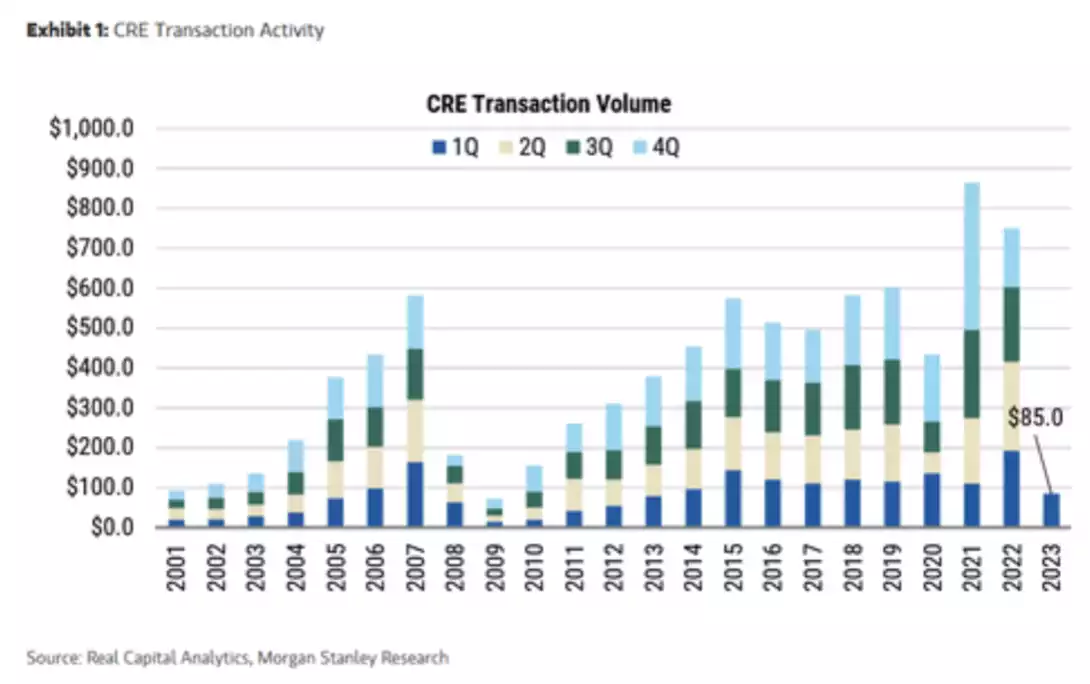

Fast forward to the present, and the CRE sector is facing an even more difficult situation, with regional banks heavily exposed. While the CRE market is smaller than residential mortgages, the current CRE problem surpasses the challenges faced by residential mortgages in the early 2000s.

Even before the pandemic, CRE had a grim outlook due to a reliance on refinancing and debt rollovers in a market accustomed to persistently low interest rates. This low-rate environment spurred overbuilding, especially in urban areas. When the Federal Reserve tightened credit before the pandemic, profitability in the CRE sector began to decline, and vacancy rates started to rise.

The situation worsened as the pandemic prompted businesses to adopt remote work, leading to a mass exodus from CRE properties. Contract renewals in 2020 saw many companies letting their leases lapse, a trend that continued into 2021 and intensified in 2022. With many in-office jobs transitioning to permanent work-from-home roles, the demand for office space plummeted, leaving property owners with vacant spaces and substantial debt.

For the banks involved, especially regional ones, the situation is dire. The loss of a high-valued asset (revenue stream from mortgage payments) has been replaced by a devalued real estate asset used as collateral. This predicament is exacerbated by the fact that CRE property values have dropped significantly, with some properties now valued at one-third of their worth just four years ago.

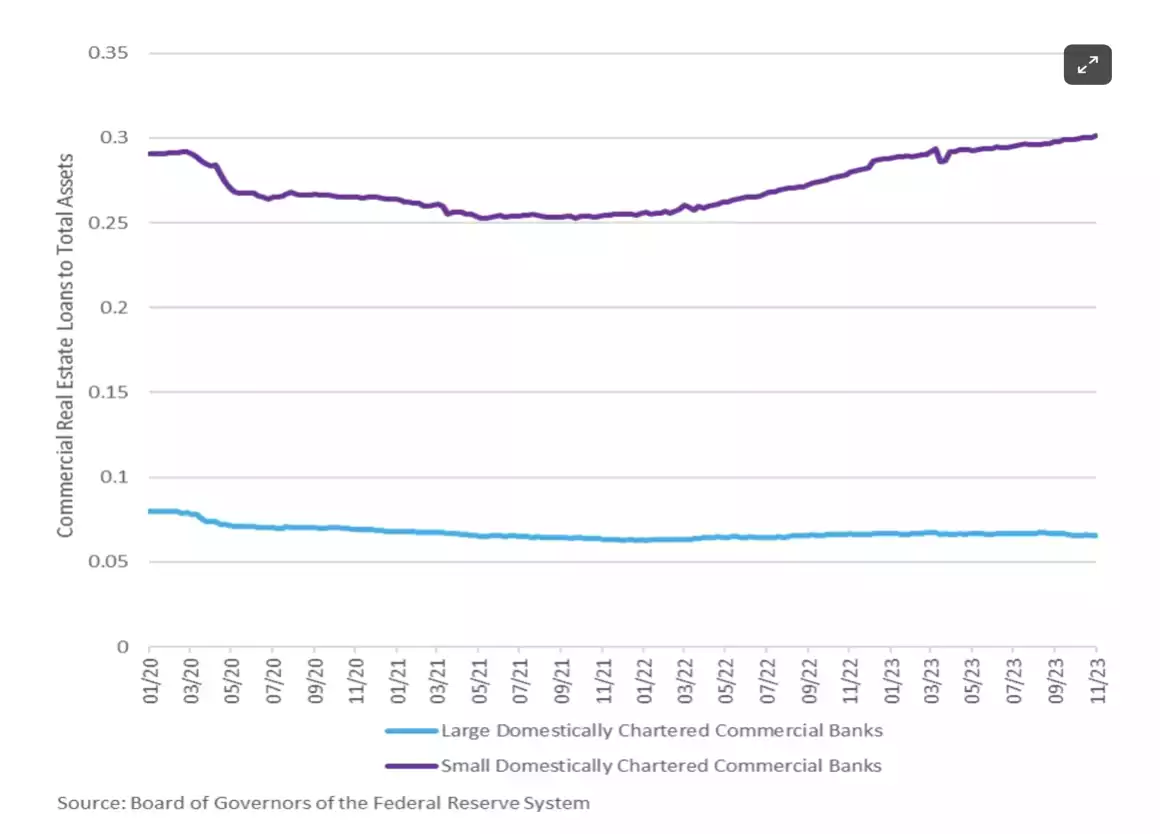

Regional banks, traditionally more exposed to the CRE market, are grappling with a challenging situation. Currently, CRE constitutes 30% of the balance sheets of regional banks, making them vulnerable to significant losses. In contrast, larger banks allocate less than 7% of their balance sheets to CRE.

If the CRE market experiences a downturn, larger banks are likely to weather relatively small losses, while regional banks could face devastation. The position of regional banks is further complicated by their need to attract more deposits, necessitating higher interest rates for depositors. However, attracting deposits requires replacing low-interest rate loans with high-interest rate ones, a task made challenging as consumers become less inclined to borrow at current expensive rates.

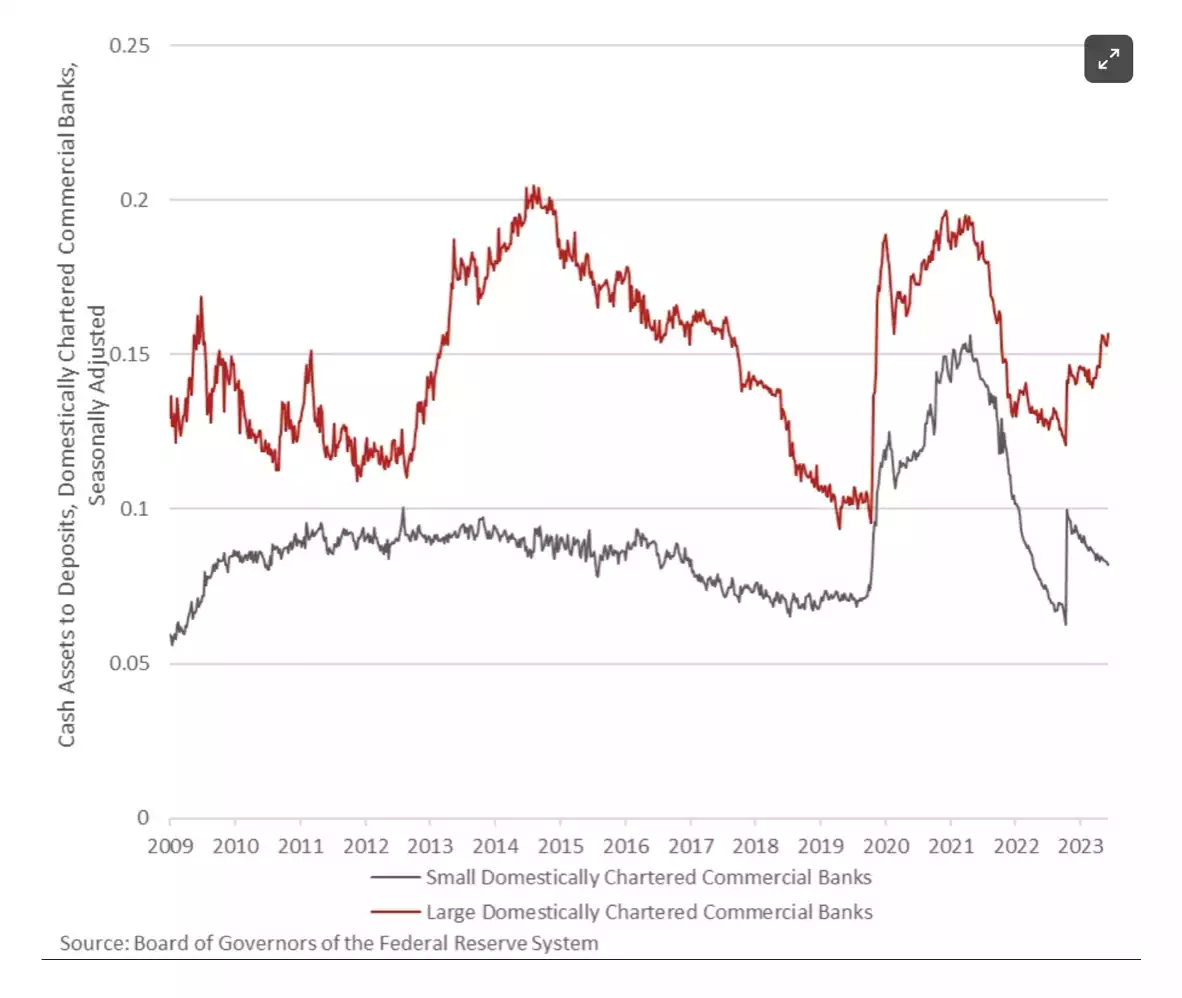

Regional banks are also caught between the dilemma of keeping cash on hand and lending it out. In a bid to address the issue, poorly positioned regional banks turned to the Fed's Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP – but ‘bailout’ by any other name) in March, borrowing $100 billion using devalued assets as collateral. However, this move only temporarily increased their cash positions, while healthier larger banks experienced a permanent boost in theirs.

The ratio of cash to deposits is crucial, as banks need sufficient cash to meet depositor demands. If banks lack enough cash, they must liquidate assets to raise funds, a situation that contributed to the troubles faced by regional banks in March.

The problem is compounded by the fact that regional banks are nearing their reserve constraint, especially once the emergency lending from the Fed expires. If these loans were to be repaid today, troubled banks would need to raise significant capital to increase their cash positions or sell off assets, a situation mirroring what led to their troubles initially.

The regional banks find themselves in a challenging position, holding a ticking time bomb in the form of the CRE market. While there's a slim chance that converting empty office spaces into housing could offer a solution, the odds of successfully navigating this complex scenario remain uncertain.