Things That Make You Go Hmmm...

News

|

Posted 22/01/2014

|

7449

BY GRANT WILLIAMS

"What a year this has been for gold.

"The price of the yellow metal fell almost 30% from its peak at the end of August a year earlier, to bombed-out lows amidst a wall of selling which included several very sharp and somewhat counterintuitive selloffs, including violent plunges in both the April-May time frame and again into year-end.

"Throughout the year, the spectre of manipulation was never far from the minds of all those involved in the gold market, whether they were crying 'foul' or asserting that, of course, there was no manipulation whatsoever and that those who suggested there might be were nothing more than conspiracy theorists, kooks, and whackos.

"The main suspects at the heart of the conspiracy theories were, naturally, the bullion banks and the central banks.

"The bullion banks, of course, have the eternal motive: profit; but what possible reason could central banks have for suppressing the price? None whatsoever, of course. The gold market is too small and too inconsequential for them to take an interest.

"And yet, rumours abounded that the bullion banks were in dire trouble and that a rising gold price could send one or more of them over the edge and into insolvency as a scramble for physical metal exposed massive short positions that had grown out of a fractional-reserve-based lending system backed (if not explicitly, then certainly complicitly) by central banks..."

Now THAT, you may well have thought, was the heart-racking, pulse-pounding introduction to my year-end look at the gold market. No preamble, no carefully constructed narrative to entice you into my latest little web, just BOOM! Straight into it.

And every word of the above makes sense based upon what we've seen happen in the past twelve months in the topsy-turvy world of element 79, which holds down the spot in the periodic table just after platinum and just before mercury.

But of course, nothing is what it seems when we are discussing gold.

That quotation at the top is the intro to the year-end review of gold that I would have written in 1999 ... had I been doing such things back then.

2013 was, in many ways, a case of been there, done that; and to understand what is happening today, it is extremely instructive to go back to 1999 and reexamine some very strange goings-on at the UK Treasury, AIG, Rothschild, Goldman Sachs, and Number 11 Downing Street.

(Cue dreamy harp music.)

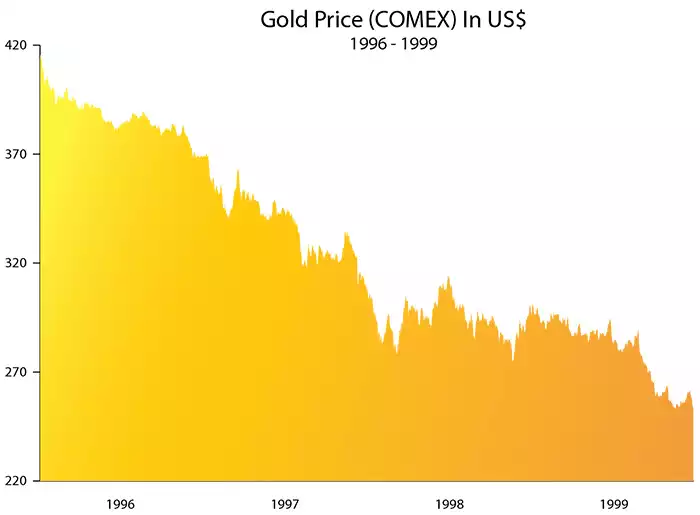

The chart of the gold price between February 1996 and August 1999 will look eerily familiar to anybody who follows the gold market closely; and for those who don't, just stick around and I'll show you what you've been missing.

After a run-up to a spike-high of $415.50 on February 2, 1996, gold began to fall. It fell fairly quickly at first, losing 3% in six trading sessions; and then the decline steadied for a while but remained consistent — until, around the end of the calendar year, gold suddenly and inexplicably spiked straight down. By the end of 1996, it had lost 11% of its value.

As 1996 turned into 1997 the price continued to fall; and the new year saw several inexplicable downdrafts of considerable size and alarming speed which, by the time the dust had settled at midnight on December 31st, 1997, had cut the value of an ounce of gold by almost a quarter.

Gold market watchers were baffled at the continued weakness in their beloved metal. They bemoaned their bad fortune and pleaded with the gods above, but neither activity made any difference — the price continued to fall. (Sound familiar?)

1998 was a fairly stable year, with the price moving little from January to December (though again, during the year there were several large falls in price that were hard to account for); and as the world entered the last year of the millennium, there was an air of stability around gold that gave hope to those battered by the consistent weakness in the gold price.

(To reiterate, I am talking about the late 1990s here, NOT the last couple of years — just in case there was any confusion.)

On the last day of 1998, gold closed at $288.25, down from $415.50 on February 2, 1996 — a fall of over 30% in three years.

You ... yes, you with the glasses at the back...

(muffled question)

No, there is very little similarity to the 37% decline in the gold price from the August 2011 high to the close on December 31, 2013.

(muffled question)

What do I MEAN? Well, obviously, any similarity is completely coincidental because there were a number of strange things happening and rumours swirling back in 1998 about bullion banks being short gold in quantities that posed a risk to them and, of course, to "the system" — whatever THAT means — so those were once in a lifetime circumstances.

(muffled retort)

Well, yes, I suppose, now that you mention THAT, there MAY be some purely coincidental similarities between the two periods, but when you hear what happened next, you'll realize that the time I'm talking about was nothing like today, because the following year (1999) a certain central bank did something quite bizarre that led directly to sharply lower gold prices and a dramatic increase in specula...

(muffled retort)

... oh look, stop it now. Keep your Bundesbank tale under your hat and we'll discuss it when I've finished. We need to get back to the main story.

If I may? Thank you.

So, as I was saying before I was rudely interrupted by young Eric there, 1999 dawned with an awful lot of antipathy towards gold after three years of poor performance. The rumour mill was operating overtime as speculation about large shorts in physical metal moved towards a crescendo, and a group of central bankers either dismissed accusations of any involvement in price suppression or refused to discuss it at all.

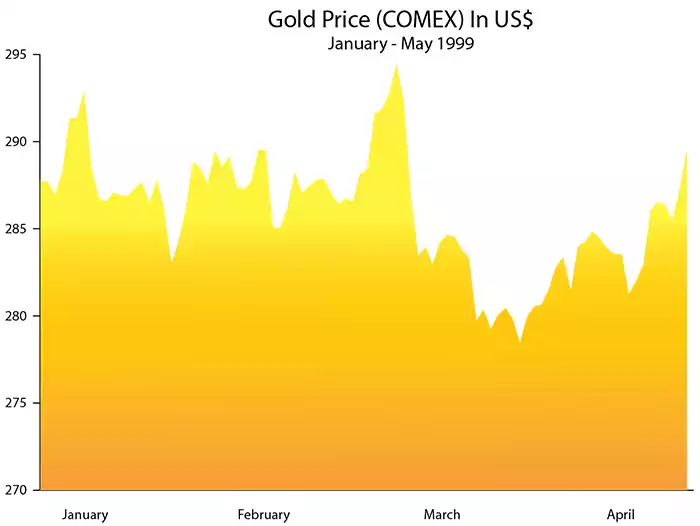

The first five months of 1999 looked fairly familiar to anybody who happened to keep a watchful eye on the gold market.

After three poor years, gold was scratching around trying to find a bottom, and it looked like it was succeeding. The path of least resistance was clearly upward, and it looked for all the world as though a bounce was in the cards, since sellers had become exhausted.

The gold price saw several quick spikes — all of which were followed immediately by sharp selloffs; but the net result was that on May 6, 1999, the gold price stood a fraction above where it had entered the year.

It was at this point that things started to get screwy.

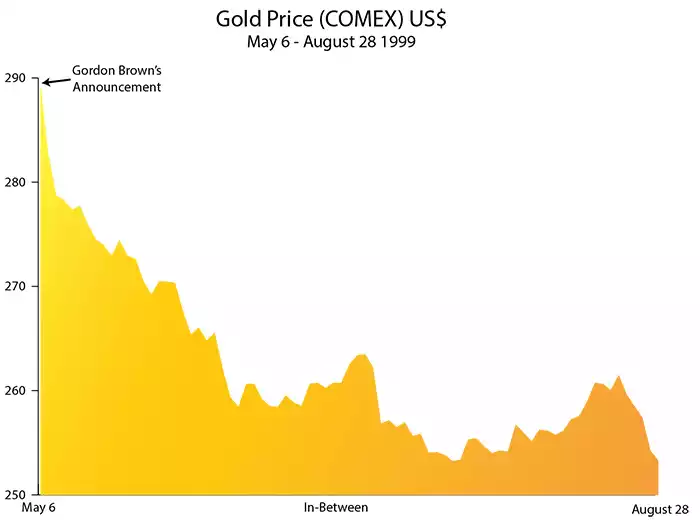

The next day, May 7, 1999, then-Chancellor of the UK Exchequer, Gordon Brown, announced that he would sell almost 400 tons of Britain's gold reserves in a series of auctions over the subsequent three-year period. Dates of those auctions were to be set well in advance.

Tense?

No, I don't mean "Are you on the edge of your seat?" The "tense" I am questioning is that used by Brown in his announcement — it was, in this case, the future progressive.

Ordinarily, when people like Brown make statements, they use a tense exclusively reserved for use by government officials and those heading up the world's major central banks: the future promissory.

This tense is constructed by taking an intended possibility and removing the words we hope and pray from the beginning of the sentence and inserting the word will in the middle.

Let me give you an example. When using the future promissory tense, the phrase "We hope and pray interest rates remain low until at least 2016" becomes:

"Interest rates will remain low until 2016."

Likewise, "We hope and pray we can unwind QE without any problems" becomes

"We will unwind QE without any problems."

Try it yourselves.

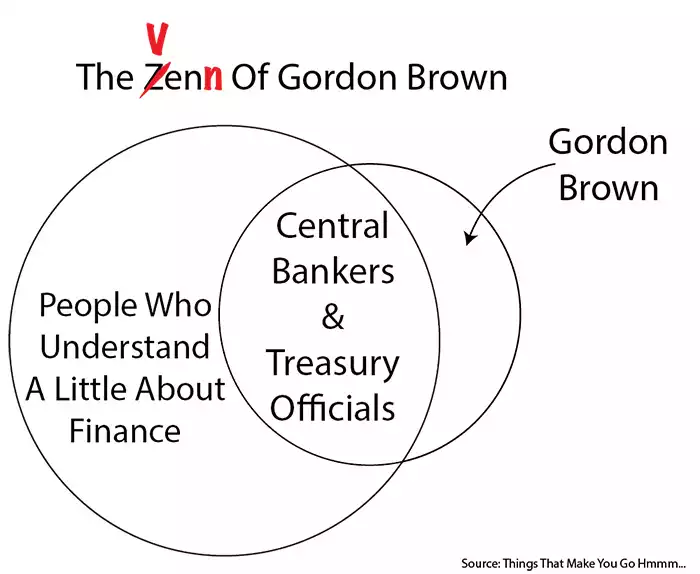

Anyway, Brown's use of the future progressive tense was particularly bizarre, because anybody who knows anything about finance, and particularly about the purchase and sale in large quantities of a price-sensitive commodity, knows that you do NOT telegraph to the market what your intentions are, because the market will then front-run you and sell that commodity short in order to generate themselves a nice healthy profit (with every dime of that profit coming directly out of the seller's proceeds).

Now, I may have been a bit naive here, but for the longest time I thought the entire set of "central bankers & treasury officials'" was a subset contained within the set of "people who understand a little about finance."

Thanks to John Venn, we can express the harsh reality rather simply:

Anyway, following Brown's extraordinary statement, I'm sure all those of you who reside firmly in the left-hand circle of that diagram can guess what happened next:

Yup! As anybody with even a rudimentary grasp of market dynamics could have predicted, the gold price fell off a cliff ... and kept on falling.

Thomas Pascoe of the UK Daily Telegraph took up the story (several years later, after a battle with the UK government over a series of Freedom of Information requests); and I have to say that for a mainstream media journalist, he did a damned fine job:

(UK Daily Telegraph, June 2012): One decision [of Brown's] stands out as downright bizarre, however: the sale of the majority of Britain's gold reserves for prices between $256 and $296 an ounce, only to watch it soar so far as $1,615 per ounce today.

When Brown decided to dispose of almost 400 tonnes of gold between 1999 and 2002, he did two distinctly odd things.

First, he broke with convention and announced the sale well in advance, giving the market notice that it was shortly to be flooded and forcing down the spot price. This was apparently done in the interests of "open government", but had the effect of sending the spot price of gold to a 20-year low, as implied by basic supply and demand theory.

Second, the Treasury elected to sell its gold via auction. Again, this broke with the standard model.

The price of gold was usually determined at a morning and afternoon "fix" between representatives of big banks whose network of smaller bank clients and private orders allowed them to determine the exact price at which demand met with supply.

The auction system again frequently achieved a lower price than the equivalent fix price. The first auction saw an auction price of $10c less per ounce than was achieved at the morning fix. It also acted to depress the price of the afternoon fix which fell by nearly $4.

Then, Pascoe dropped the hammer:

It seemed almost as if the Treasury was trying to achieve the lowest price possible for the public's gold. It was.

We'll come back to Pascoe's article a little later, but in the meantime it's back to 1999 and the rumour mill...

There was consternation in the gold community and anguished cries that, as usual, there was a vast conspiracy in play here. Those rumours of large shorts held by a couple of big players in the bullion market just wouldn't go away, but nobody could quite put their finger on what was going on — although a couple of slightly curious names were being whispered in the gold pits: AIG (remember them?) and NM Rothschild.

Brown's series of auctions over the following three years emptied most of the UK's gold from the Bank of England's vaults, depressed the price to levels previously unthought of and, according to those of a more conspiratorial mindset, achieved something else. Something hidden, something unknown.

But what?

The probable answer wouldn't begin to appear from amidst the fog until mid-2004, when, a couple of months apart, a couple of very quiet and matter-of-fact announcements were made, which we will get to shortly. In the meantime, if the UK Treasury was trying to achieve the lowest possible price for its gold, it was doing admirably — right up until September 26, 1999, when a backlash against Brown's actions crystallized in Washington DC through the signing of the Washington Agreement on Gold.

(Wikipedia): Under the agreement, the European Central Bank (ECB), the 11 national central banks of nations then participating in the new European currency, plus those of Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, agreed that gold should remain an important element of global monetary reserves and to limit their sales to no more than 400 tonnes (12.9 million oz) annually over the five years September 1999 to September 2004, being 2,000 tonnes (64.5 million oz) in all.

The agreement came in response to concerns in the gold market after the United Kingdom treasury announced that it was proposing to sell 58% of UK gold reserves through Bank of England auctions, coupled with the prospect of significant sales by the Swiss National Bank and the possibility of on-going sales by Austria and the Netherlands, plus proposals of sales by the IMF.

The UK announcement, in particular, had greatly unsettled the market because, unlike most other European sales by central banks in recent years, it was announced in advance. Sales by such countries as Belgium and the Netherlands had always been discreet and announced after the event. So the Washington/European Agreement was at least perceived as putting a cap on European sales.

So that's clear. What is interesting are the criticisms of the agreement, as posted on the same Wikipedia page:

•The agreement is not an international treaty, as defined and governed by international law.

•The agreement is a sui generis, gentlemen's agreement among Central Bankers, of doubtful legality given the objectives and public law nature of Central Banks.

•The agreement resembles a cartel that materially affects the supply of gold in the global market. In this regard, the agreement stretches the borders of antitrust legislation.

•The agreement was negotiated behind closed doors. Information was not provided to the public and relevant stakeholders were not afforded the opportunity to comment.

•The agreement does not contain formal mechanisms for re-negotiation. Trends in international law regarding public participation and access to information should inform the re-negotiation process, scheduled for 2004.

Sounds pretty much par for the course, if you ask me; but that's the world we've allowed to be created by the governments and central banks of the world while we watch American Idol.

Anyway, with Brown's sales well and truly underway and the market price suitably depressed, the announcement from Washington caused a small problem. Limiting sales of a commodity has the opposite effect to the pre-announced sales by the UK Treasury, and the inevitable ensued.

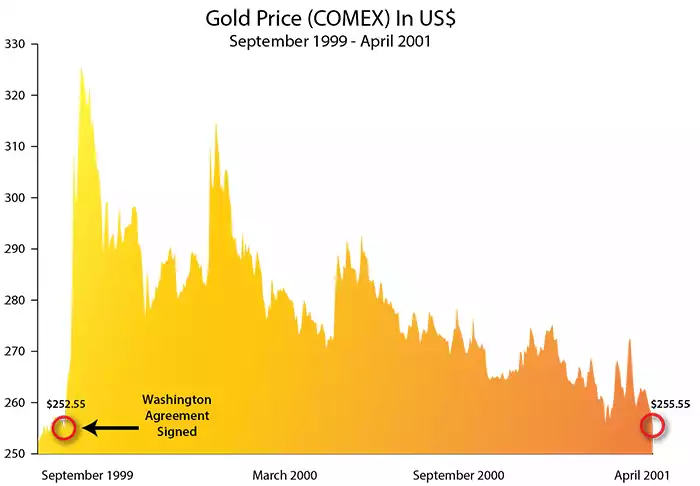

The gold price, freed temporarily from the shackles of the huge overhang Brown had created, soared, as you can see from the chart below:

...and that — assuming the rumours were correct and there were a couple of entities short a lot of gold and looking to cover into a falling price — created another big problem.

The post-Washington Agreement spike would have caused severe problems for anybody short gold, and if those problems caused any kind of systemic risk, then they were problematic for central banks and governments, too.

Of course, all this was nothing more than conjecture ... at the time.

BUT several years later a conversation surfaced that had involved Bank of England Governor Eddie George, shortly after the Washington agreement was signed in 1999. Whereupon many of the doubts surrounding the motives behind the strange doings in the gold markets disappeared like my buddy Whipper West 20 seconds before the bar tab is presented:

(Jesse's Café Américain): In front of 3 witnesses, Bank of England Governor Eddie George spoke to Nicholas J. Morrell (CEO of Lonmin Plc) after the Washington Agreement gold price explosion in Sept/Oct 1999. Mr. George said "We looked into the abyss if the gold price rose further. A further rise would have taken down one or several trading houses, which might have taken down all the rest in their wake.

Therefore at any price, at any cost, the central banks had to quell the gold price, manage it. It was very difficult to get the gold price under control but we have now succeeded. The US Fed was very active in getting the gold price down. So was the U.K.

You want to find a smoking gun at the crime scene? Well this one has fingerprints on it and the words "Eddie George, Governor of the Bank of England" carved into the butt.

Case closed. Except...

With none of this ever having been officially acknowledged, the whole business has juuuuust enough uncertainty surrounding it to enable those who don't want to know to put their fingers in their ears and repeat "la-la-la-la-la."

As you can see from the chart above, the following 18 months saw the gold price "managed" steadily lower, despite several large spikes in price as the natural forces of supply and demand threatened to overrun the Bank of England — and US Federal Reserve-led intervention.

Eventually, enough force was brought to bear to get the gold price back to its pre-Washington Agreement level. This was in large part due to the sales by Brown of the UK's gold stash. When the smoke had cleared and the auctions were completed, Brown's Treasury conducted an autopsy review of the process that would end up costing the UK taxpayer roughly £17 bn in lost profits at gold's peak in 2011, and even in the immediate aftermath a cool £175 mn.

That review was bound to be scathing, right? Wrong:

(UK Daily Telegraph): Chancellor Gordon Brown and his Treasury officials have used an internal review to pat themselves on the back for selling more than half of Britain's gold reserves, despite the fact the process lost the taxpayer around £175m.

Huh? Say what?

The news that one of the world's major central banks was selling its reserves contributed to a collapse in the gold price which was a serious blow to the market.

However, the Treasury argues that the auction was a great success. Its review, which has been published on an obscure part of the Treasury website, claims: "The UK Government's sales programme has clearly demonstrated that auctions provide a transparent and fair method for selling gold and similar types of asset."

Oh come ON!! Really?!

I know government officials have a predilection for trying the Jedi Mind Trick on us, but this is utterly ridiculous.

Luckily, not everybody was fooled:

Peter Hambro, who runs the eponymous gold company, said: "The idea the auction was a success is completely ridiculous. The point is the Treasury called the bottom of the market with uncanny accuracy. They have forgotten that gold is meant for times of trouble."

Amazingly (though this is government we are talking about here, so the bar over which one has to hurdle to be classified as "amazing" is lower than Kim Kardashian's level of self-respect), despite the fact that the price fell to a 20-year low after the auction process was announced and then soared 30% after its conclusion, the Treasury claimed success based solely upon the fact that "on average, they achieved a price within 75 cents, or 0.3pc, of the market price."

I'm sorry, but when you conduct sales like that, you SET the market price. Idiots.

The article continues:

The review states: "It is not apparent from the data that the market was systematically depressing the price of gold in the run-up to the auctions. Nor is there any evidence that the price of gold systematically rose following the auctions."

Not apparent? To WHOM?? As for evidence that the price of gold systematically rose following the auctions, I would suggest looking at ...... the price!

IDIOTS.

The Bank of England sold 395 tonnes of gold, raising about $3.5 billion. The money has since been invested in euros, yen and dollars as a way of diversifying risk.

The review concludes: "Above all, the programme successfully delivered a one-off and permanent reduction in risk on the net reserves as a result of the better diversification achieved."

It's just too painful to listen to sometimes.

Anyway, back to our story.

With things having calmed down and a nice slug of central bank gold having been dumped on the market in order to suppressmanage the price, the focus was off the gold market once again.

Now, do you remember those two very quiet and matter-of-fact announcements I told you we'd get to? Well here they are:

First, on April 14, 2004, came this:

(Reuters): NM Rothschild & Sons Ltd., the London-based unit of investment bank Rothschild, will withdraw from trading commodities, including gold, in London as it reviews its operations, it said on Wednesday.

Perfectly innocuous.

Then on June 1st, a few weeks later, a similar and equally low-key announcement hit the wires:

(Reuters) — AIG International Ltd., part of American International Group Inc., will no longer be a London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) market maker in gold and silver, the LBMA said on Tuesday."

OK ... now Rothschild was an old, established name in the metals markets, but AIG? The derivatives-driven basket-case/liability insurance giant? What the hell were THEY doing up to their eyeballs in gold?

Well, one of the most respected names in the bullion markets is that of Arthur Cutten, proprietor of Jesse's Café Américain (if you follow gold and silver but don't have that page bookmarked, I'd recommend you do so right now.) In a post he wrote in March 2010, Arthur asked a pertinent question:

(Jesse's Café Américain): Brown's Bottom Is an Enormous Issue In the UK: Was This a Bailout of the Multinational Bullion Banks Involving the NY Fed?

The sticky issue is not so much the actual sale itself, but the method under which the sale was taken and who benefited.

There has been widespread speculation that the manner in which the sale was conducted and announced was in support of the nascent euro, which Brown favored. This does not seem to hold together however.

There is also a credible speculation that the sale was designed to benefit a few of the London based bullion banks which were heavily short the precious metals, and were looking for a push down in price and a boost in supply to cover their positions and avoid a default. The unlikely names mentioned were AIG, which was trading heavily in precious metals, and the House of Rothschild. The terms of the bailout was that once their positions were covered, they were to leave the LBMA, the largest physical bullion market in the world.

Ahhh.... now we're getting somewhere... The two names about whom speculation was rife did, in fact, quietly leave the LBMA a couple of years after the fuss had died down.

Curiouser and curiouser.

Arthur finished with a flourish:

The manner in which the sale was conducted, and the speed at which it was undertaken, without consultation of the Bank of England, made many of the City of London's financiers a bit uneasy.

"Uneasy," indeed.

In any case, for whatever reason — perhaps to avoid a major disruption in the bullion markets, maybe to avert a bankruptcy by AIG and/or Rothschild or potentially even "the collapse of the system" (oh how I tire of that hackneyed phrase); it really doesn't matter — the price of gold was taken down precipitously and the market was spooked.

Whether a bunch of the UK's gold went to settle contracts outstanding against AIG and Rothschild may never be known; but on the balance of probability, and understanding how important gold is at the centre of our financial system, I'm willing to bet SOMETHING untoward went on in 1999.

Which brings us to this past year and the startling parallels between 2013 and the period that concluded with those UK Treasury sales and the disappearance from the gold pits of AIG and Rothschild.

In July of 2013 I wrote a piece called "What If?" which I closed by asking the following question:

The gold price has been falling heavily for several months, but when the need to own gold jumps again — and it will, this is a long way from over — all the weird and wonderful pieces to this jigsaw puzzle that have been dropped onto the table will slot neatly into place.

What if, when that happens, there isn't enough gold to go around?

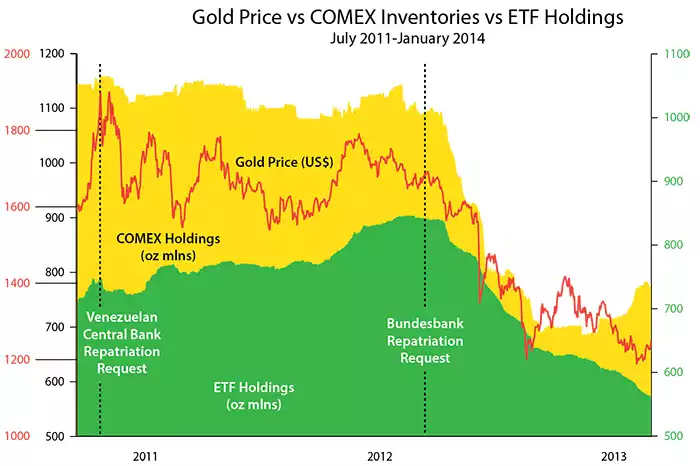

The centrepiece of that particular letter was a chart that plotted the gold holdings at the COMEX, the known holdings of gold ETFs, and the gold price. It also showed the moment when the Bundesbank made their now-famous request that 300 tonnes of gold be repatriated from the vault at the NY Fed to the Bundesbank in Frankfurt.

I have had many requests to update that chart, so here it is:

As you can see, not much has changed. ETF holdings have continued to decline, as has the gold price, while stocks at the COMEX have increased slightly. However, with the help of my buddy Nick Laird of Sharelynx(THE place to find any precious metals chart you could possibly want, plus a lot more), I'll show you in just a sec how even this situation may not be what it seems.

But before we get to that, let's recap the striking similarities between 1999 and 2013 to get a feel for what the events of this past year may mean going forward.

2012 saw gold mark time, just as it did during the first five months of 1999, but once 2013 arrived, things changed immediately, after an announcement by a central bank that sent tremors through the precious metals markets.

In 1999 it was Gordon Brown's extraordinary statement that the UK would hand billions of dollars to the bullion banks by selling 400 tonnes of gold at pre-announced auctions, and in 2013 it was the German Bundesbank's repatriation request that shook up the markets.

Throughout 1999 and beyond, there were hundreds of tonnes of gold being hoovered up at ever-declining prices. It was not easy to say where that gold was going, but the available evidence — which was subsequently bolstered when Eddie George took maybe one too many trips to the courtesy bar — suggested it was going to fill huge holes in the balance sheets of AIG and Rothschild.

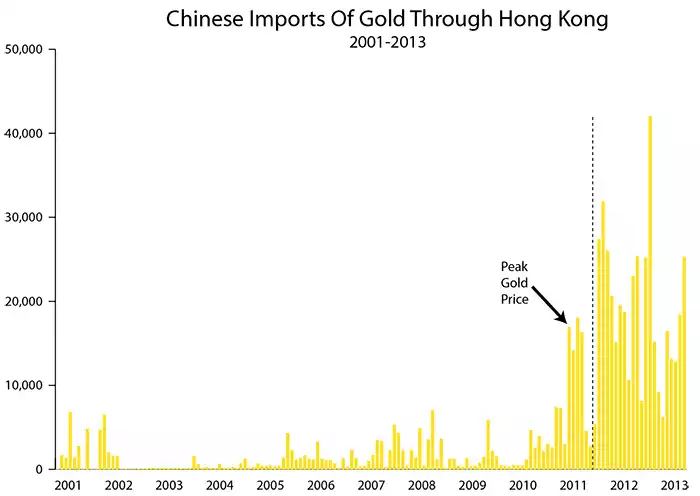

In 2013, the evidence was overwhelming that the physical gold backing the futures contracts that cascaded down on the COMEX in suspiciously large and totally price-insensitive quantities was headed in one direction and one direction only — east.

Gold imports into China through Hong Kong went through the roof. Massively inflated exports of gold from the UK to Switzerland (home of the world's finest smelters) strongly suggested that bullion was being withdrawn from the LBMA warehouses and sent (via Switzerland) to China. Meanwhile, in India, despite frantic efforts by the government to stem the flow of gold, there was no stopping the tidal wave of demand for the yellow metal as insurance against a weakening rupee and ... well, because to Indians gold IS money.

Period.

But it's the events at the COMEX warehouses that we'll focus on next, because there are yet more strange shenanigans taking place that suggest all is not as it should be.

First, it's important to understand how gold is stored at those warehouses.

There are two categories under which a holder can store gold at the COMEX warehouses: registered and eligible.

Registered gold is that which has been registered with a bullion dealer and can be made available for delivery in the exercise of a COMEX futures contract.

Eligible stocks conform to the standards of delivery, BUT they are not available for delivery into a futures contract that has been exercised.

Eligible ounces can be moved quite easily to registered status via the issuance of a depository receipt or warrant by a bullion dealer, although the move in the opposite direction is a little more troublesome.

With that explained, let's take a look at the two categories as they stood at the end of 2013. We'll begin with eligible ounces:

As you can see, the number of eligible ounces in COMEX warehouses has climbed in recent months (as we saw in the overall numbers in the chart on page 15). This means that more gold is being removed from the deliverable gold stock and put safely into designated private hands.

When we look at the registered stocks, however, we see the potential for a huge problem:

In short, every ounce of registered physical metal in the warehouses has almost 120 paper claims on it via open-interest futures contracts. That means there may not be enough gold to go around if certain events transpire — and the events we're talking about here are hardly asteroid-strikes-Earth kind of stuff.

Speculation about a failure to deliver on the COMEX has floated around many times before and has never come to anything; but as the registered stocks have continued to dwindle, I and many others have warned that just because it hasn't mattered, definitely doesn't mean it won't.

Well, this week Tres Knippa, a veteran futures trader, took a look at the registered stocks on the COMEX and outlined just how close to the bone things have gotten. (You can watch Tres' interview in the videos section on page 40.)

According to Tres, with stocks on COMEX at the levels they have reached, if just a single entity were to demand physical delivery of a position-limit long in gold futures, meeting that demand would absorb 81% of the registered ounces left in the warehouse. If two were to do so ... well, the only person I can think of who would need the math done for him is Gordon Brown, so I'll leave it to you to work out.

But where has all this physical gold been going?

Well, we've mentioned China and the increase in imports through Hong Kong, which incidentally looks like this:

We've mentioned India's stringent capital controls aimed at slowing the importing of gold, but all those have done (predictably) is send smuggling levels through the roof:

(Reuters): In a sign of the times, whistleblowers who help bust illegal gold shipments can get a bigger reward in India than those who help catch cocaine and heroin smugglers....

"There has been a several-fold increase in gold smuggling this year after restrictions from the government, which has left narcotics behind."

From travellers laden head-to-toe in jewellery to passengers who conceal carbon-wrapped gold pieces in their bodies — in the mistaken belief that metal detectors will not be set off — Indians are smuggling in more bullion than ever, government officials say, driven by the country's insatiable demand for the metal.

That suggests official data showing a sharp fall in gold buying, which has helped narrow India's current account gap, may significantly underestimate the real level of gold flows.

The World Gold Council estimates that 150 to 200 tonnes of smuggled gold will enter India in 2013, on top of the 900 tonnes of official demand.

But the elephant in the room is that Bundesbank repatriation request; and as 2013 came to a close, things got even more intriguing as yet more inexplicable information came to light.

You'll remember that, when it demanded its 300 tonnes of gold back in January, the Bundesbank was told it would have to wait seven years. No explanation was given and, apparently, none was demanded.

In "What If?" I did the math:

(TTMYGH): The Bundesbank wants to repatriate 300 tonnes of gold which is, of course, sitting, untouched at the Federal Reserve in New York.

That 300 tonnes equates to 300,000 kilograms.

A Boeing 747-400, set-up in a standard cargo freighter configuration has, according to its manufacturer, a maximum payload of 112,630 kg, a range of 5,115 miles (4,445 nautical miles) and a typical cruising speed of 0.845 Mach (560 mph).

The distance between New York and Frankfurt is 3,858 miles.

So, in essence, the German government could charter three 747-400s, send them to New York, load them up with their gold and still have 37,890 kg of space left.

To avoid claims of bending the narrative to make a point, I went a step further:

Now, I'm aware that there is a maximum amount of gold which is insurable in any one shipment (though I don't know exactly what that amount is); but if we go to extremes and assume it's as little as a single tonne (1,000kg), that would mean — using the same three 747-400s in our previous example — a total of 300 flights or, with each plane flying once per day, 100 days.

But not seven years.

No, not seven years.

Not even close.

But at the rate the gold actually came back to Germany in 2013 (from both New York and Paris), it will take much, much longer than seven years:

(Zerohedge): Yesterday Buba head Jens Weidmann told Bild that gold valued at €1.1 billion has been repatriated so far. Putting a weight to this number: to date the Bundesbank has received shipments of a paltry 37 tons of gold from its existing storage place in either New York or Paris to Germany: "The gold reserves of the country will be stored in Frankfurt because it has a special storage with the corresponding equipment," said Carl-Ludwig Thiele, a Bundesbank board member.

The repatriated amount over the course of all of 2013 represents just over 5% of the total stated target of 700 tons, and is well below the 87.5 tons that the Bundesbank would need to repatriate each year if it were to collected the 700 tons ratably every year in the 8 year interval between 2013 and 2020.

Pathetic.

But in fact it gets much worse.

This morning, an article appeared on Zerohedge suggesting that, of the 37 tonnes repatriated in 2013, 32 came from Paris — meaning that just 5 TONNES made its way across the Atlantic:

(Zerohedge): The official explanation was as follows: "The Bundesbank explained [the low amount of US gold] by saying that the transports from Paris are simpler and therefore were able to start quickly." Additionally, the Bundesbank had the "support" of the BIS "which has organized more gold shifts already for other central banks and has appropriate experience — only after months of preparation and safety could transports start with truck and plane." That would be the same BIS that in 2011 lent out a record 632 tons of gold...

We wonder, how exactly is a gold transport "simpler" because it originates in Paris and not in New York? Or does the NY Fed gold travel by car along the bottom of the Atlantic, and is French gold transported by a simple Vespa scooter across the border to Germany?

Supposedly, there was another reason: "The bullion stored in Paris already has the elongated shape with beveled edges of the 'London Good Delivery' standard. The bars in the basement of the Fed on the other hand have a previously common form. They will need to be remelted [to LGD standard]. And the capacity of smelters [is] just limited."

So... New York Fed-held gold is not London Good Delivery, and there is a bottleneck in remelting capacity? You don't say...

I'm not sure the EXACT thickness that is required of a plot to start people believing that there is something funny going on; but if we're not there yet, I'm hopeful we're not far away. Maybe one more ridiculous statement by one more central bank is all it will take to start the wheels turning in the media. We'll see.

Amongst the skeptical minority (in which I firmly place myself), the news of the paltry shipments to Germany was enough to fan all kinds of flames, but what happened next made it seem as though one of the following three things is true of these guys at the Bundesbank:

1) They are demonstrating their complete lack of understanding as to how the gold market works.

2) They are filled with such hubris that they don't care how ridiculous they sound.

3) They are hiding behind "state secrecy" laws that mean they answer to nobody. The Bundesbank announced that the pitiful amount of gold returned to Frankfurt from the USA had first been melted down and recast in New York, supposedly to ensure the bars conformed to LGD (London Good Delivery) specifications.

<coughcoughbullshitcough>

Now these revelations may not seem to amount to much, but they open yet another crazy can of worms and make it even harder to believe that the gold supposedly sitting in the vault at the NY Fed is actually there.

Naturally, this information sparked a firestorm, and front and centre in that storm was Peter Boehringer, president of the German Precious Metal Society and co-initiator of the Repatriate our Gold campaign, who published an open list of questions raised by the Bundesbank's curious behaviour:

(Peter Boehringer): The public is still waiting for answers to crucial questions like these:

•What kind of gold bars were melted? Original material from the 1950s and '60s?

•How can the Bundesbank hint in its press release that some of the old bars already met the LGD specifications when those specifications were not defined and made a standard for central bank bars until 1979?

•Why has the Bundesbank not published a bar number list of the old bars? How can there be security concerns about bars that no longer exist? Why has the Bundesbank not published a bar number list of the newly cast bars?

•Who exactly melted the bars? Where exactly was this melting performed? Is there a smelter at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York?

•Who witnessed the melting and recasting of the bars?

•Are there any reports on this in writing, with a valid signature? By whom?

•And especially: Why was it deemed necessary to perform this action in the United States as opposed to Frankfurt or nearby Hanau, where there are some of the best facilities in the world for metal probing, melting, and recasting? Had these actions been performed in Germany in a fully transparent manner, it would have been so easy for the Bundesbank to dismiss all questions from "paranoid gold conspiracy theorists."

These central banks just refuse to help themselves, I'm afraid. They NEVER seem to do the transparent thing where gold is concerned (ironic, given Gordon Brown's insistence on "open government" surrounding the UK gold sales), always leaving themselves open to accusations of foul play.

Of course, what that MIGHT just mean is that there HAS been foul play and they have no alternative but to brazen it out and hide behind a wall of "no comments" and claims of a need for security.

The gold in every central bank's possession around the world is the property of the citizens of that country — not of the incumbent politicians or central bankers. Consequently, if the people want it audited, there shouldn't be any reason to say no ... unless...

2013 was an absolutely seismic year for gold, but the way in which the tectonic plates shifted has yet to be fully understood.

I firmly believe that in the years to come, when we look back at the great game being played in gold, we will pinpoint January 16, 2013, as the day when it all began to unravel.

That day, the day the Bundesbank blinked and demanded its bullion, will be shown to be the beginning of the end of the gold price suppression scheme by the world's central banks; and then gold will go on to trade much, much higher.

The evidence of suppression is everywhere, though most refuse to believe their elected officials are capable of such subterfuge. However, the recent numerous scandals in the financial world are slowly forcing people to realize that anything and everything can be manipulated.

Libor, mortgage rates, FX — all were shown to be rigged markets, but NONE of them have the importance that gold has at the centre of the financial universe, yet all of them are far bigger markets than gold and therefore much harder to rig.

Gold is a manipulated market. Period.

2013 was the year that manipulation finally began to unravel.

2014? Well now, THIS could be the year that true price discovery begins in the gold market. If that turns out to be the case, it will be driven by a scramble to perfect ownership of physical gold; and to do that you will be forced to pay a lot more than $1247/oz.

Count on it.