The Pentagon Pizza Index: What Late-Night Pizza Orders Tell Us About Gold

News

|

Posted 19/02/2026

|

2906

When the Pentagon orders pizza, investors take note.

There’s an unusual indicator trending across social media this week. It’s not a new economic model or a central bank announcement. It’s pizza.

The Pentagon Pizza Index is an informal, decades-old observation that late-night pizza deliveries to the Pentagon, the CIA and the White House tend to spike just before major military events. It sounds absurd, yet it has shown an uncanny pattern over time. And right now, it’s flashing again.

The Origin Story

The concept traces back to a Domino’s franchise owner, Frank Meeks, who ran stores near Washington D.C.’s government buildings in the 1980s.

Meeks observed that whenever late-night Pentagon orders surged, something significant often followed. Orders doubled the night before the invasion of Grenada in 1983. The same pattern appeared before Panama in 1989. On 1 August 1990, the CIA placed a single-night record of 21 pizza orders. The next morning, Iraq invaded Kuwait.

The logic is straightforward. When a crisis unfolds behind closed doors, officials work late. When they work late, they order food. The pizza wasn’t intelligence itself; it was a by-product of intensified decision-making.

The Modern Version

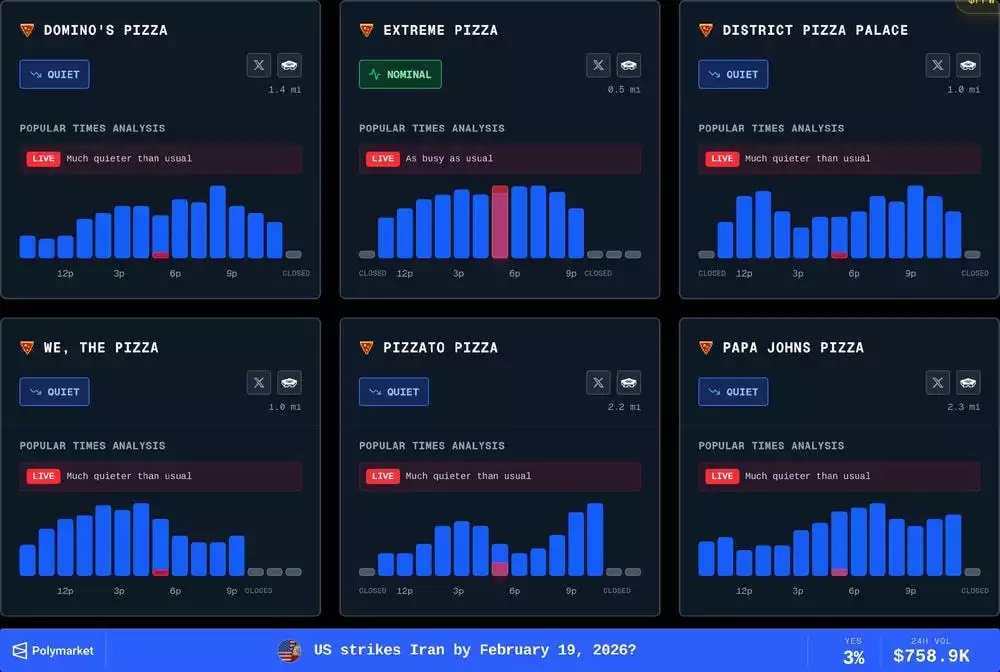

What began as a quirky anecdote has evolved into a real-time tracking exercise. Accounts such as the Pentagon Pizza Report on X now monitor Google Maps foot-traffic data for pizza shops near the Pentagon, flagging sharp deviations from normal patterns.

The recent track record has drawn attention. In April 2024, unusual late-night activity at a Papa John’s near the Pentagon coincided with Iran launching drones into Israel. In June 2025, another surge was flagged roughly an hour before Israel bombed Iran. In early January 2026, elevated activity preceded U.S. strikes in Venezuela.

None of this proves causation. But the recurring pattern is difficult to ignore.

Why It’s Trending Now

The index is back in focus amid a rapidly escalating standoff between the United States and Iran.

On 16 February, Iran commenced large-scale naval manoeuvres in the Strait of Hormuz, the narrow waterway through which around 20 per cent of the world’s oil supply passes each day. The drills reportedly included testing anti-ship cruise missiles and drone swarms.

By 18 February, the U.S. had deployed the USS Gerald Ford and USS Abraham Lincoln carrier strike groups to the Persian Gulf, marking the largest concentration of American naval power in the region in nearly a decade.

Washington has given Tehran a two-week window to narrow diplomatic gaps, with President Trump reserving the option to use force. The Eurasia Group now assigns a 65 per cent probability of a direct military strike on Iranian infrastructure by April.

Gold’s Response

When geopolitical risk rises, capital reallocates. And it often reallocates to gold.

On 18 February, gold reached US$5,019.60 per ounce, a level that would have seemed extraordinary just two years ago. Earlier in January, bullion briefly touched US$5,594.82 before retracing.

This move isn’t solely about Iran. Several forces are converging.

Geopolitical risk is becoming structural. From Russia-Ukraine to Venezuela to tensions in the Strait of Hormuz, the global security backdrop has shifted. Markets are no longer pricing in isolated disruptions; they are adjusting to a more persistent risk environment.

Central banks continue to accumulate. Countries across the Global South, including China, India and Turkey, have been adding to gold reserves at the fastest pace in decades, deliberately diversifying away from the U.S. dollar. Goldman Sachs has cited this demand as a key driver behind its US$5,400 year-end forecast.

Rate cuts are anticipated. Markets are pricing in at least two Federal Reserve rate cuts in 2026. Lower rates reduce the opportunity cost of holding non-yielding assets, improving gold’s relative appeal.

Traditional safe havens are under scrutiny. Government bonds, historically the alternative defensive asset, face growing questions around sovereign debt sustainability, including in the United States. When the so-called risk-free asset carries fiscal risk, diversification becomes more important.

The Strait of Hormuz Factor

The current tensions carry particular weight because of geography. The Strait of Hormuz is the world’s most critical oil chokepoint.

Any disruption to shipping through the Strait transmits quickly to energy markets. Higher oil prices feed inflation. Persistent inflation supports gold. The feedback loop can build momentum rapidly.

Some analysts suggest that if Iran continues drills without interfering with commercial shipping, gold could ease back towards US$4,500 on de-escalation. Conversely, even a limited military exchange could push gold towards US$6,000 and oil back into triple digits in short order.

What It Means

The Pentagon Pizza Index is not a financial model. It isn’t peer-reviewed, and the Department of Defense has publicly dismissed it. Confirmation bias is a valid concern. We remember the spikes that precede major headlines and forget those that do not.

Yet the index endures because it reflects a broader truth. Observable human behaviour can sometimes signal shifting conditions before formal announcements are made.

Whether you view the Pizza Index as novelty or insight, the underlying message is clear. Geopolitical uncertainty is unlikely to fade quickly. In that environment, gold’s role remains consistent.

It cannot be printed, sanctioned or defaulted on. It sits outside the political system. Central banks understand this. Institutional capital understands it. Increasingly, private investors do as well.

When uncertainty rises, gold remains a core portfolio consideration. The Pizza Index may be the most colourful signal, but it is the broader shift in global risk that matters.

Gold prices referenced in this article are indicative and based on international spot prices at the time of writing. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial advice