The Cobra Effect and the Unintended Consequences of Government Interference

News

|

Posted 25/09/2025

|

1968

The "Cobra Effect" refers to the unintended and often counterproductive consequences of well-meaning policies—particularly when perverse incentives encourage behaviour that undermines the original goal.

We’ve seen several such outcomes in Australia. Consider the VET-FEE HELP scheme, designed to help Australians upskill for better employment. Instead, it left many burdened with significant debt, lowering their standard of living rather than improving it. The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), while conceived with the best of intentions, has now become so overloaded that children with developmental needs often face long delays in receiving support—delays that can entrench, rather than address, lifelong disabilities. Carbon taxes, intended to shift the world towards cleaner energy, have largely punished developed nations with cleaner industries and higher energy prices, while pushing production to countries like Thailand, where only 12% of energy comes from renewables compared to Australia’s 40%. Even welfare itself is argued to create dependency rather than resilience—locking more people into long-term reliance on government support.

So what is the Cobra Effect, and what lessons should we take from it? At what point does government stop trying to fix inequality through redistribution and start enabling prosperity through productivity—creating more opportunity, more wealth, and a more secure future?

The Origin of the Cobra Effect

The term comes from British colonial India in the 1870s. In an attempt to reduce the number of dangerous cobras in Delhi, authorities offered a bounty for every dead cobra. Locals began breeding cobras purely to kill them and claim the reward. When the government realised what was happening and cancelled the bounty, breeders released the now-worthless snakes—worsening the problem they were trying to solve.

In the 1960s, German economist Horst Siebert coined the term “Cobra Effect” to describe economic policies that lead to opposite or damaging outcomes. It’s now a common term for policy failures driven by misaligned incentives.

Welfare and Unintended Dependency

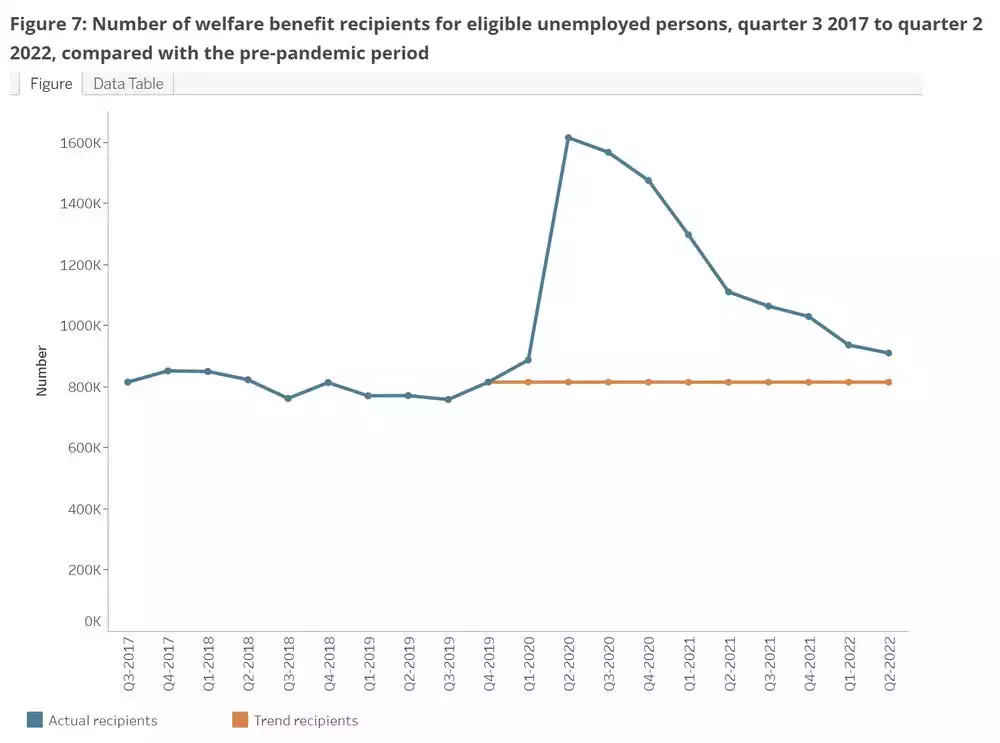

Government spending, particularly since COVID, has grown unsustainably. A contributing factor may be the government’s own messaging during the pandemic—effectively encouraging people not to work through stimulus and welfare measures. Since then, the number of Australians on welfare has remained above trend.

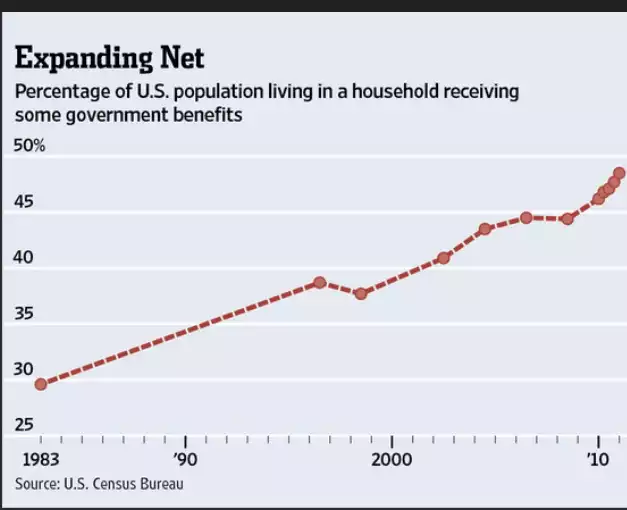

Welfare tends to reinforce itself. Once people are in the system, they’re more likely to stay in it. In the US, Census Bureau data from 2010 showed that households receiving welfare rose from around 29% in 1983 to 49%—highlighting how difficult it can be to unwind such systems once they take root.

NDIS – A Case Study in Policy Gone Awry

The NDIS is facing growing scrutiny—and with good reason. What began as a visionary program to support Australians with disability has in many cases become a system riddled with inefficiencies, distortions, and even fraud. The Cobra Effect is at work on multiple fronts:

- Explosion in Autism Diagnoses and Early Childhood Entries

The scheme’s generous support for developmental delays and autism has led to a sharp rise in diagnoses—not due to a true increase in prevalence, but because access to support is now tied to diagnosis. Since 2013, nearly half of new autism cases have been driven by the NDIS. Annual autism support costs have soared from AU$1 billion to a projected AU$9.5 billion by June 2025, with 1 in 8 boys aged 5–7 now on the scheme.

Cobra Effect: A policy meant to boost early intervention has instead created diagnostic inflation and dependency on a specialised system, bypassing mainstream support.

- Fee-for-Service Model Encouraging Over-Servicing

Providers are paid by the hour, incentivising volume over value. This results in excessive support hours, inflated staff ratios, and plans designed around billable activity—not meaningful outcomes.

Cobra Effect: Intended to promote choice and efficiency, the model encourages overspending and provider self-interest.

- Perverse Incentives for Fraud and Unethical Referrals

The structure has enabled fraud, with criminal groups inflating invoices and colluding with facilitators. Kickbacks for referrals have also emerged.

Cobra Effect: Designed for participant empowerment, the lack of oversight has created a lucrative target for exploitation.

- Disincentives for Mainstream and Foundational Supports

With state services underfunded, the NDIS became the only viable option for many families—even those with milder needs. This has diverted investment from inclusive education and broader community support systems.

Cobra Effect: A well-funded NDIS has inadvertently hollowed out the very systems meant to prevent long-term dependency.

- Plan Renewal Pressures and Appeal Backlogs

Participants often rush to spend their funds before reviews to avoid future cuts, fostering inefficiency and adversarial interactions with the agency.

Cobra Effect: Intended as a measure of accountability, the review process has instead driven fear, stress, and poor resource allocation.

The big question is not if the NDIS will be scaled back—but when. Much like the vocational education collapse, we may see a sudden policy shift once the costs and distortions become politically unsustainable. In attempting to address inequality and need, the government may have built yet another welfare system that does the opposite of what it set out to achieve.