Smoot Hawley Tariffs – Not an Argument Against Tariffs

News

|

Posted 05/03/2025

|

2124

There is much debate about the effectiveness of tariffs, and we have not previously taken a stance on this issue. In a quest to look at a more comprehensive argument either for or against tariffs, we started with the 1930s, when economists used to argue against tariffs. In 1930 the Smoot-Hawley Act was passed putting tariffs on imports into the US. Did the tariffs cause the Great Depression, as some have argued? Or could the case against tariffs be influenced by historical bias, attributing their impact to circumstantial timing that aligns with the current economic narrative? Was the Great Depression made worse by the Tariffs or was the Great Depression caused by an economic structural response to the Industrial Revolution and the electrification of the world that followed closely behind it. If it was a structural response – is it possible we are about to see a similar ‘Great Depression’ this time brought on by the AI revolution?

Smoot-Hawley Act

The argument against tariffs fits squarely in a period when the ‘Great Depression’ began in 1930, where in response to collapsing demand and rising unemployment tariffs were implemented around the world. In 1930, following countries like France issuing of tariffs, the United States followed with the Tariff Act of 1930 known otherwise as the Smoot-Hawley Tariff. The Tariffs sat around 20% on around 20,000 goods.

The Act saw the 2nd highest tariffs in the US’ history and saw many other countries retaliate with their own tariffs. This led to a reduction in US exports by 67%.

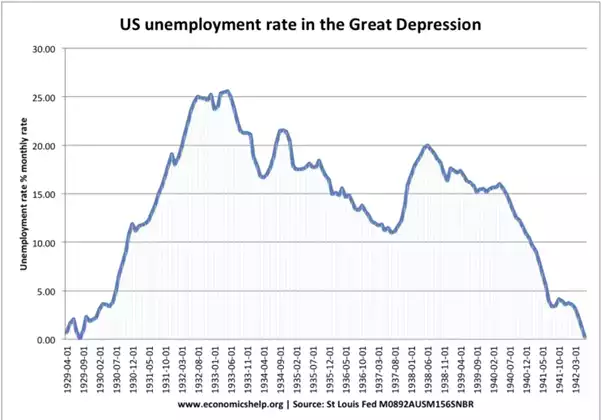

In 1930, following the 1929 stock market crash unemployment was already rapidly rising, from almost full employment in 1929, to around 5% by the time Smoot-Hawley was passed, this rapid rise in unemployment and the subsequent 6 months following where it rose to nearly 11% could not be blamed on this act, the trajectory was already there. The question really becomes did the tariffs make the Great Depression worse - it clearly wasn’t the cause as the trajectory was already there.

Electrification and Productivity Gains

The previous 3 decades have seen huge advancements in agricultural productivity with the mass adoption of rail, cars and tractors replacing horses and miles leaving around 20% of farmland that had previously been needed to feed the horses and mules available for more agricultural produce production. In the late 1920s the electrification of manufacturing had led to huge productivity gains in manufacturing. As rails, cars and machinery were built labour usage lifted throughout the 1920s, but as these goods started to be used for production of consumer items including food, labour usage in these industries began to drop. The tariffs were a response to overcapacity in the world as the labour dynamic didn’t keep up with the change

Much like today, there is a mini-industrial revolution happening with AI. Since 2000, the economy has seen tech booms, and now AI booms, as labour is moved to these industries to build capacity. We appear to be moving towards a scenario reminiscent of the 1930s, where the leaps and bounds made in ‘electrifying the economy’ are now being utilised to replace labour in AI-vulnerable industries. Are tariffs therefore just a response to the excess capacity we are about to see?

History is Not the Answer

Smoot-Hawley doesn’t appear to give the answers we need to assess whether tariffs work or not. What it does do is shed light on a period that seems to have some relevance to the potential impact of the AI revolution on the labour market. How nations navigate it this time will be a telling response to how the next 10 years shapes the future of mankind.

As history has shown, economic uncertainty and structural shifts in labour markets can have profound and unpredictable effects. In times of such change, tangible assets like precious metals have historically served as a hedge against economic instability. Gold and silver, in particular, have long been valued for their ability to preserve wealth and provide security when markets become volatile. As we move into an era where AI-driven disruptions could reshape industries and employment, investors may once again turn to precious metals as a safeguard against uncertainty and financial turbulence.

Watch the Ainslie Insights video discussion of this article here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RKOd4uSiFlw