No More Rate Cuts

News

|

Posted 17/11/2025

|

1293

If you’ve just bought a new home or you’re banking on a rate cut to lift the return on your investment property, it might be time to reset your expectations. The weak jobs data last month fuelled hopes of easier monetary policy. But yesterday’s bumper employment print has abruptly shut that window.

The Reserve Bank has been clear about what it needs before loosening policy: productivity gains. And right now, the Bank sees Australia at a supply-constrained juncture, with years of under-investment by firms creating an economy operating close to full capacity. In such an environment, any lift in demand—whether from migration or an economic upswing—risks reigniting inflation and keeping rates higher for longer.

With inflation above trend, employment strong, and capacity stretched, it’s fair to ask: is the next move in rates up, not down? And if Australia fails to close the investment gap, could we be heading toward a period uncomfortably reminiscent of the 1980s: low growth, persistent inflation, and rising joblessness?

Employment Is Still Too Strong for Relief

This week’s labour market numbers delivered another surprise, with the unemployment rate falling to 4.3%. That follows September’s shock jump to 4.5%—a move that briefly pushed markets to price in earlier rate cuts.

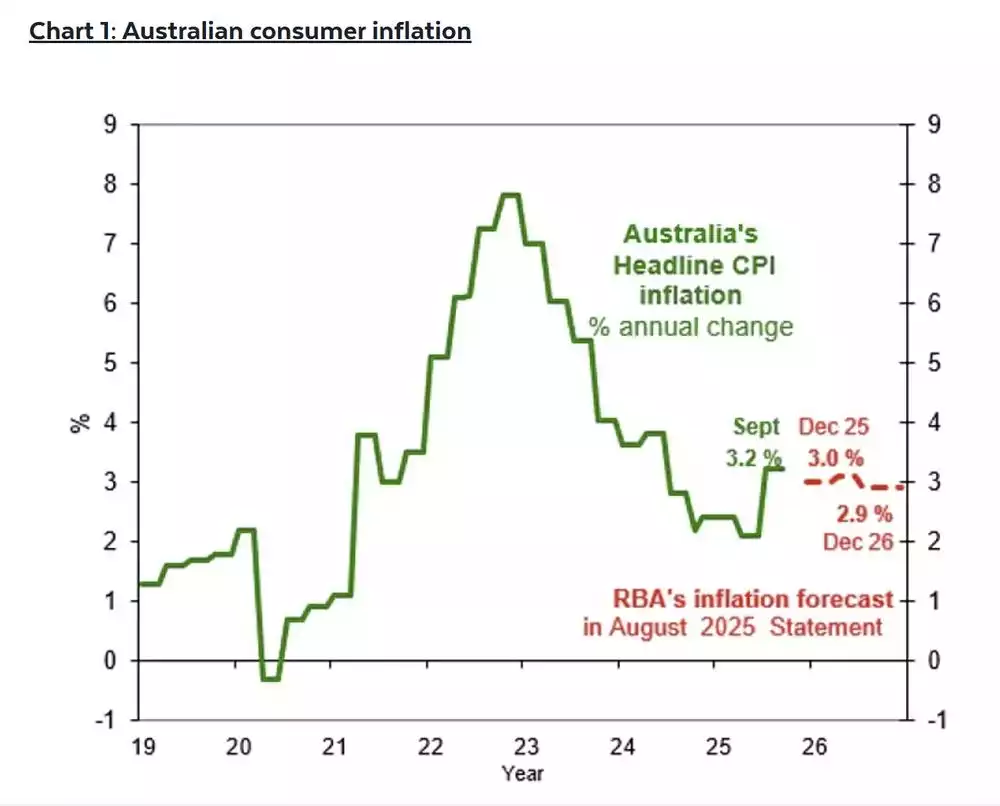

The RBA’s dual mandate is clear: full employment and 2–3% inflation. Inflation looked like it was trending back into that band earlier this year, with June delivering 2.1%. But by September it had re-accelerated to 3.2%.

Strong employment combined with pricing pressure means the Bank is now effectively locked in place. Cuts are off the table—and the risk of a hike is rising.

What exactly is the RBA waiting for? Deputy Governor Hauser spelled it out this week: productivity gains, something Australia has lacked for more than a decade.

‘On the Rail or Off to the Races?’

Last week, RBA Deputy Governor Hauser delivered a speech at the UBS Australasia Conference titled ‘On the Rail or off to the Races?’, casting serious doubt on the prospect of further rate cuts. He outlined a troubling mismatch in the current economic backdrop: demand is accelerating, but firms have not invested enough in productive capacity to lift supply.

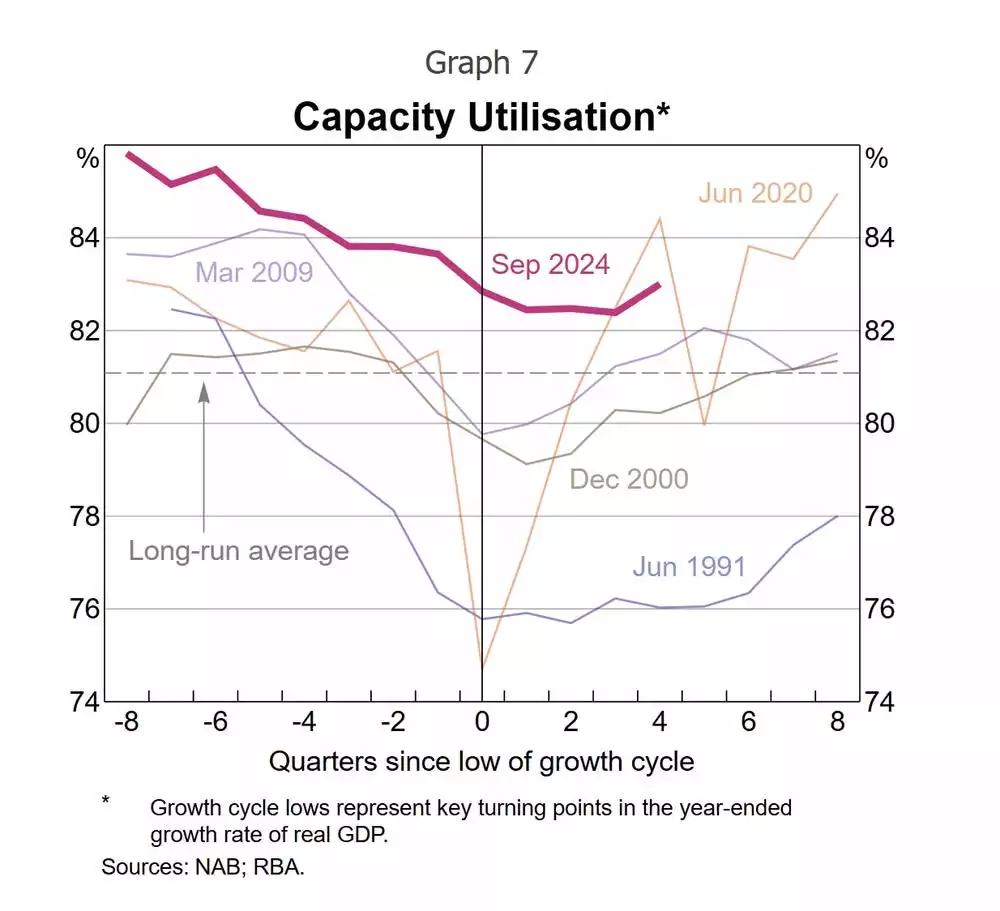

Hauser argues that Australia has endured years of weak productivity growth, leaving the economy with almost no spare capacity. If demand rises from here, the lack of available supply will simply push prices higher, keeping inflation stubborn and forcing the RBA to maintain—or even increase—rates.

He compared today’s conditions to the early 1980s, noting:

"Our central estimate suggests that demand was slightly above potential output at the time GDP growth started to pick up last year — the tightest economic backdrop to a recovery since at least the early 1980s."

Hauser argues that today’s problems are the result of a “cumulative effect of rapid demand growth in 2021–2022, the deliberately cautious monetary policy strategy of more recent years, and — importantly — weak growth in supply.”

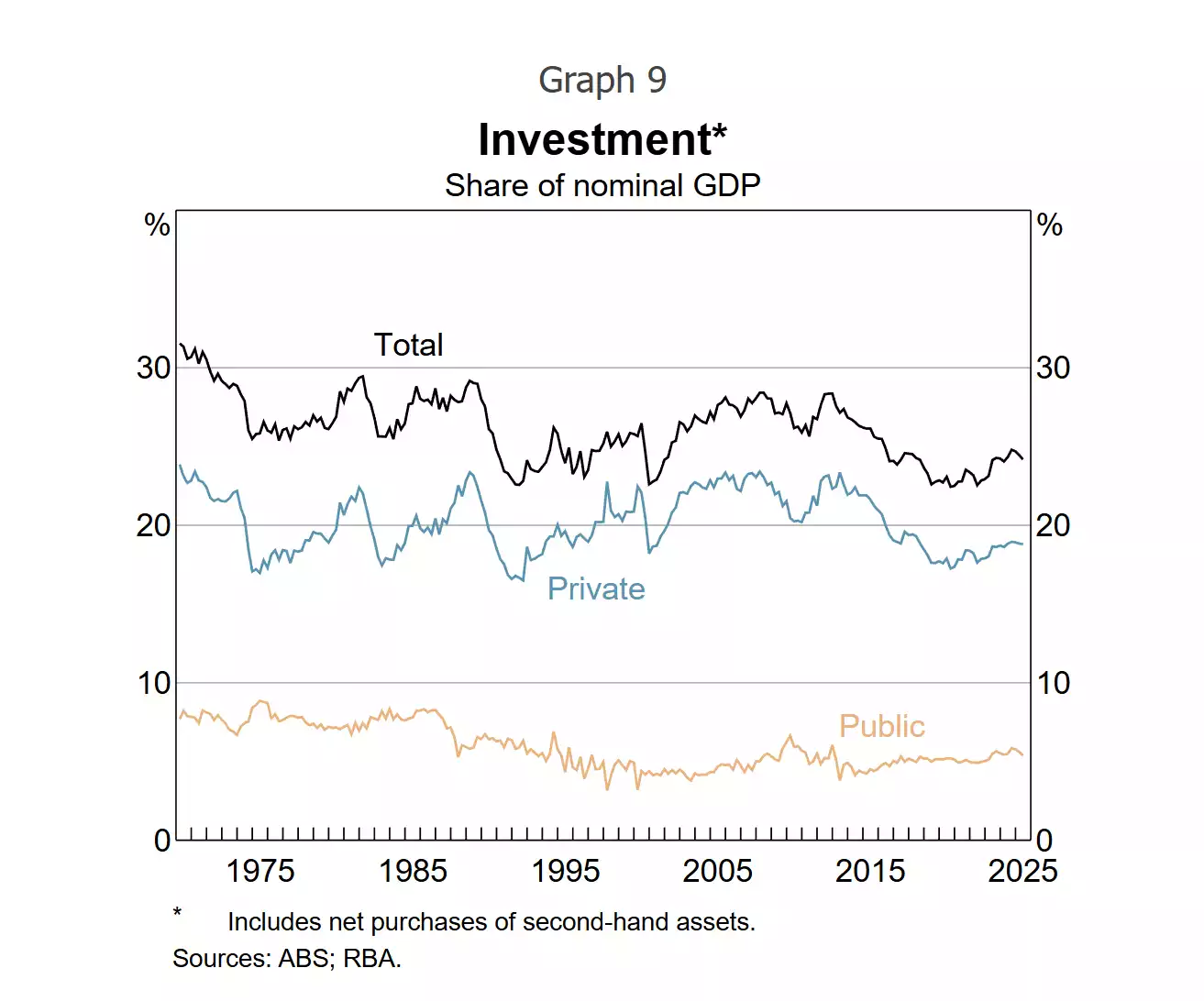

Rather than flowing into productive industries, capital and labour have been absorbed by the property market. High household wealth, strong migration and a resilient banking system have funnelled investment toward housing, a sector that delivers relatively low productivity returns. This misallocation has left the broader economy short of the investment needed to expand capacity.

Compounding the issue is Australia’s well-known preference for dividends. Hauser suggests that, instead of reinvesting in new equipment, technology and expansion, many profitable firms have been returning capital to shareholders to keep their stocks attractive — starving the economy of the investment required to lift long-term productivity.

Labour dynamics add another layer. Construction, being a comparatively low-skilled but relatively well-paid sector, draws younger workers straight out of school. As Hauser puts it:

"Being a comparatively low-skilled sector, most of the younger talent naturally gravitates towards building jobs, easier to get working straight from high school, rather than developing technical skills that can help prop up other industries."

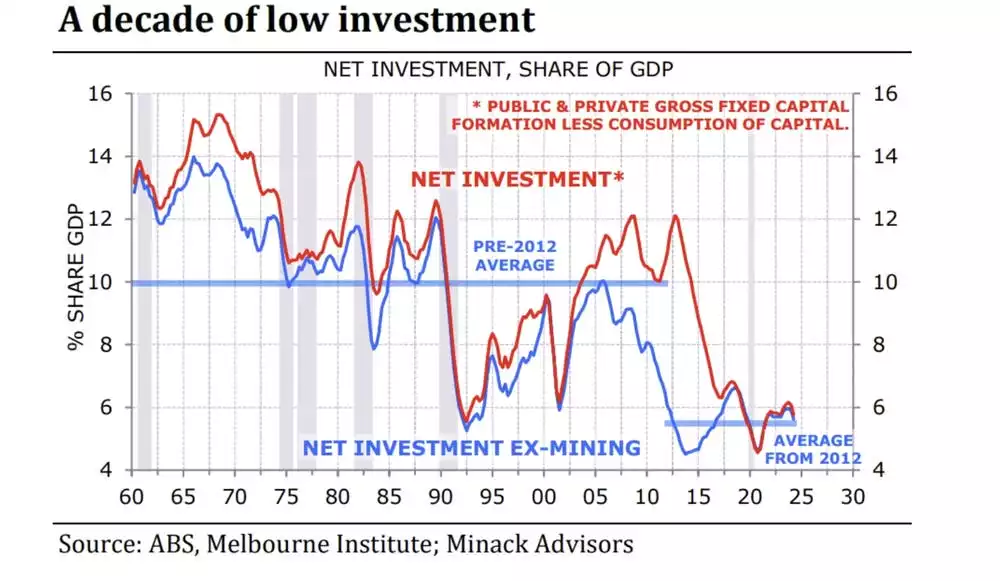

The RBA maintains that productivity growth is the single most important factor in avoiding a slide into stagflation. Yet Australia has endured a decade of weak productivity gains. While incentives like the COVID-era instant asset write-off did temporarily encourage investment, private-sector investment in productive capacity has since fallen back below trend — leaving the economy with insufficient supply-side strength at a time when demand remains robust.

Private capital investment has been trending lower since around 2015 — a shift that closely mirrors Australia’s decline in productivity gains over the same period.

Housing versus Productivity

Australia’s exceptionally high household wealth, strong banking system and inflows of foreign capital and labour have all helped drive property prices to record highs. But economists warn this has come at a cost: investment has been diverted away from parts of the economy with far greater productive potential.

RSM Australia economist Devika Shivadekar notes that strong demand for housing creates a constant pull for labour:

“High demand for property means there's always a need for labour. Being a comparatively low-skilled sector, most of the younger talent naturally gravitates towards building jobs, easier to get working straight from high school, rather than developing technical skills that can help prop up other industries.”

Others argue the relationship between housing and productivity is even more indirect. AMP deputy chief economist Diana Mousina points out that Australia’s poor productivity growth in the housing sector itself has constrained the broader economy’s ability to expand supply:

“The poor productivity growth in the housing sector has also hurt [Australia's] ability to supply. The two are so interconnected. I [also] think our tax system and our migration system has created the housing problem that we are in.”

On the investment side, Betashares chief economist David Bassanese highlights the role played by incentives facing Australian shareholders:

“I would say the love affair with dividends and franking instead perhaps has [hurt productivity] as it encourages firms to pay out dividends [rather] than reinvest for growth.”

Yet reinvestment is precisely what the Reserve Bank sees as essential for lifting productivity and avoiding a slide toward stagflation. Without stronger investment in technology, equipment and skills, the economy will continue to struggle to grow supply fast enough to meet rising demand.