Mt Isa Copper Smelter and Refinery Under Threat

News

|

Posted 31/07/2025

|

1838

As Trump's tariffs and a shift toward deglobalisation challenge Australia's “dig it, don’t do it” economy, the country is starting to resemble a mine without a smelter—or a boat without a paddle. First, it was the nickel refinery in Townsville, then the aluminium and steel smelters requested government support, and now Glencore is seeking assistance to continue copper processing in Australia.

Australia is competing against heavily subsidised, coal-fired economies—where globalisation has been tempered by strategic nationalism, not sacrificed at its altar. As both government policy and Glencore put Mt Isa on the brink, it raises the question: is it time for Australia to do more than just dig?

Copper Mine Closure and Processing Under Pressure

Yesterday marked the final day of operations at Glencore’s Mt Isa copper mine. However, copper processing has continued at the nearby refinery and in Townsville. Glencore is now seeking government support to keep those facilities operational—a move Mt Isa Mayor Danielle MacRae says reflects a distorted and manipulated global market.

“Glencore is not a charity,” she said.

“They're competing in a distorted global market manipulated by foreign countries intent on cornering the copper supply chain.”

The Mt Isa smelter is also Australia’s largest producer of sulphuric acid—a critical input for fertilisers. If it closes, Australian farmers may become reliant on imports for yet another vital product.

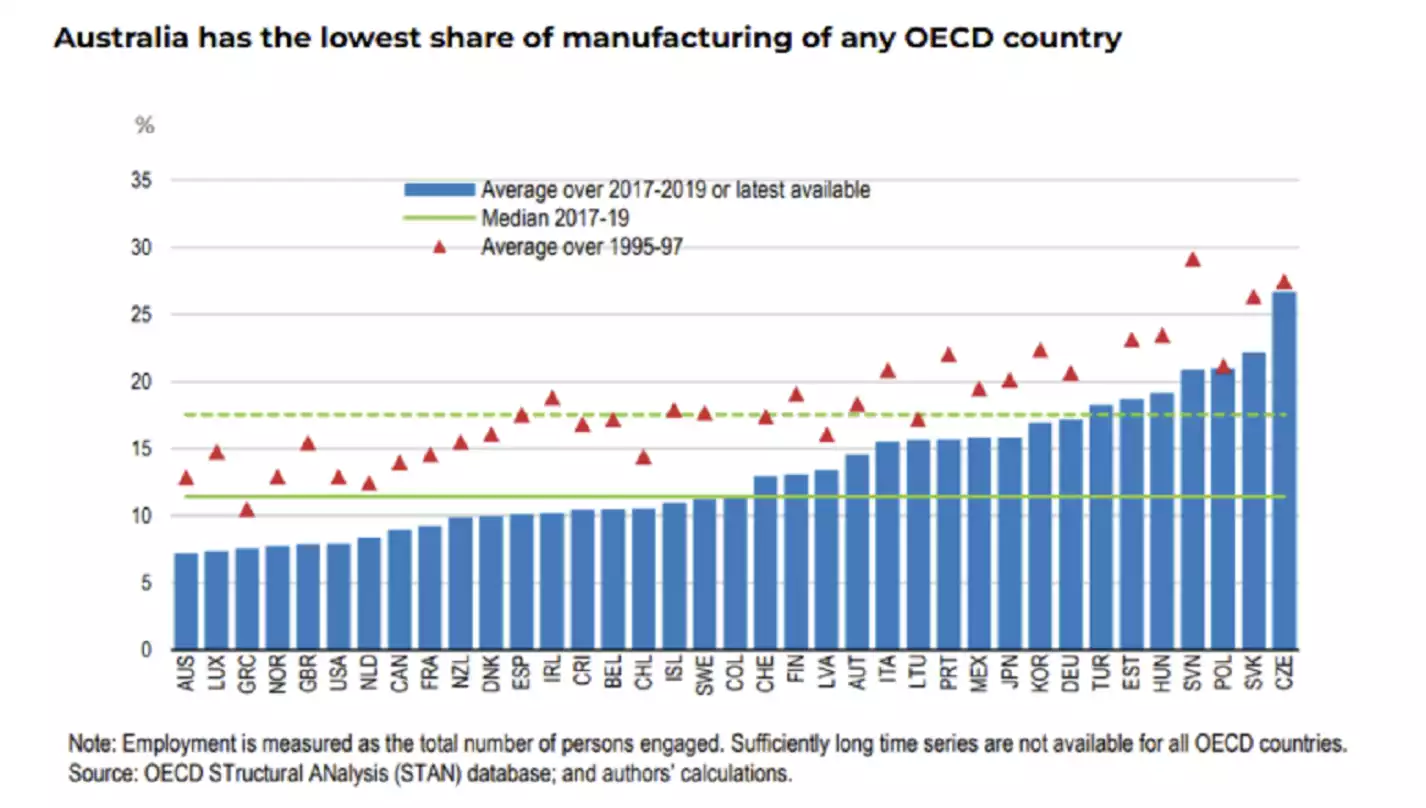

Manufacturing is an ecosystem of interlinked inputs and outputs. When one output—like petrol refining—is shut down, or an input—like gas for plastics—is throttled, the entire system begins to falter. With manufacturing now a smaller share of GDP than in Luxembourg—a financial hub with no mineral or agricultural base—Australia’s industrial capacity appears on the verge of collapse in a deglobalising and increasingly hostile world.

Ironically, while the Albanese government champions "green manufacturing", copper remains a foundational material for everything from EVs to solar panels, if local processing ends, we’ll soon be importing that too.

Glencore cites rising costs—primarily labour and energy—and an increasingly uncompetitive environment marked by excessive red tape and regulatory uncertainty. The message is clear: policy settings are undermining both productivity and sovereign capability.

Australia’s Innovation and R&D in Decline

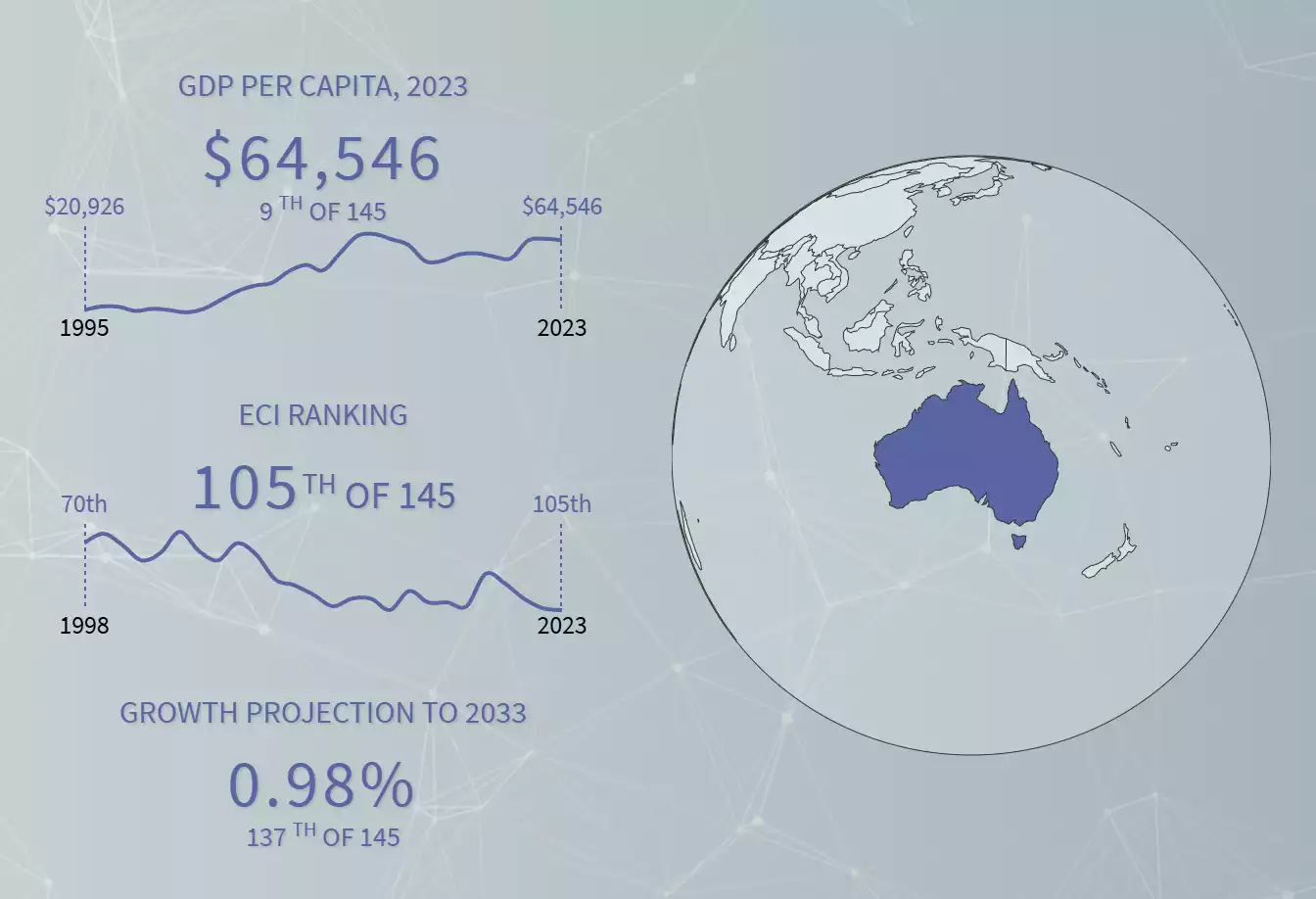

Australia’s economic decline isn’t just about smelters—it’s systemic. The country has fallen from 63rd in the Harvard Kennedy School’s Economic Complexity Index in 2000, to 93rd in 2015, and now sits at 105th—trailing Senegal, Botswana and Bangladesh.

As Tim Cheston, Senior Research Manager at the Growth Lab stated:

“So again, falling from 63rd to 102nd shows that we’re consistently going in the wrong direction within this measure of economic complexity.”

Australia’s projected growth over the next decade is now under 1%, placing us 137th out of 145 countries. That’s behind most of the developing world—only narrowly ahead of Guinea, Chad, Congo, and Nigeria.

Innovation is driven by making things cheaper, faster, lighter, and greener. In the 1980s, Mt Isa pioneered the Isasmelt furnace and the Jameson Cell—world-leading Australian technology that cut energy use and improved efficiency. We were greener because we were making.

Now, we ship our ore offshore to be processed using our coal, in more carbon-intensive plants, only to import the finished product back—and call it sustainable.

Successive governments have somehow convinced an economy powered by 45% immigration that we’re more green by producing less. That may be the greatest act of national innovation we’ve achieved in recent years.

Let’s see what 137th place gets us.

Watch the insights video inspired by this article here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qQPO3xskprw