Monetary Policy Failure Since COVID-19

Insights

|

Posted 04/09/2025

|

2038

Bond markets are sending a clear warning. Long-duration bond prices are collapsing, driving long-term interest rates well above current cash rates. UK 30-year bond yields are at their highest since 1998, France since 2011, and the US since 2008—levels not seen since past economic crises: the Dotcom bust, the GFC, and the US debt ceiling crisis.

It raises a serious question: is monetary policy failing?

Keynesian Theory Revisited

John Maynard Keynes laid out his theory of monetary policy in The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936), built on three key concepts: the investment multiplier, the marginal efficiency of capital, and interest rates. His framework sought to explain economic fluctuations around a long-term equilibrium, typically from high unemployment toward full employment. Keynes concluded that central banks should aim to steer the economy toward this equilibrium.

In Australia, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has three statutory objectives:

- the stability of the currency of Australia;

- the maintenance of full employment in Australia; and

- the economic prosperity and welfare of the people of Australia.

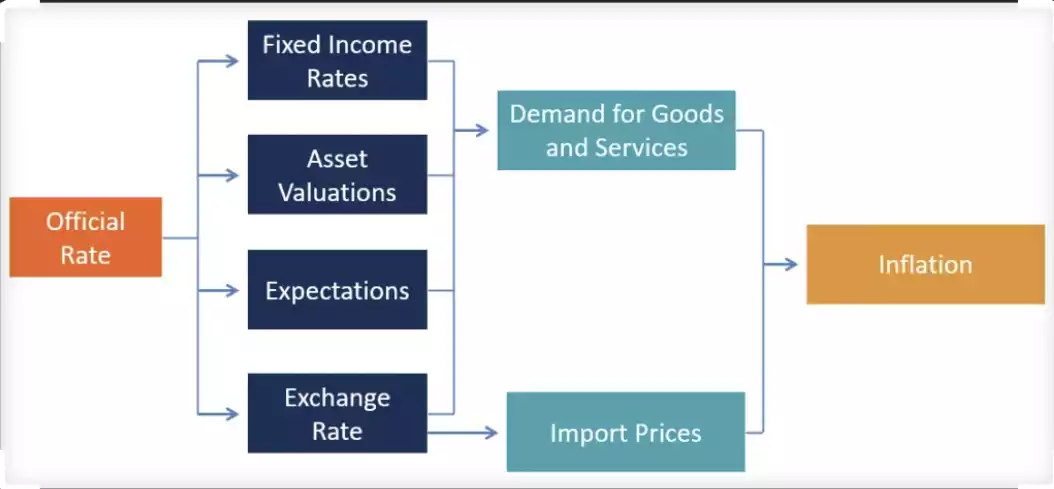

To pursue these goals, the RBA adjusts interest rates—its primary monetary policy tool. These settings influence the economy through the “Transmission Mechanism”, which operates via five main channels:

- Interest Rate Channel: Lower rates reduce borrowing costs, encouraging spending and investment.

- Exchange Rate Channel: Lower rates can weaken the dollar, making exports more competitive.

- Wealth Effect Channel: Cheaper money inflates asset prices, boosting consumer confidence and spending.

- Bank Lending Channel: Lower policy rates reduce borrowing costs for banks, enabling cheaper credit to households and businesses.

- Expectations Channel: Forward guidance shapes expectations; if people believe rates will stay low, they’re more inclined to spend now.

These mechanisms aim to smooth the economic cycle, though their effectiveness depends on the alignment of monetary and fiscal policy, as well as public expectations

COVID’s Shock and the RBA Response

During COVID, Australia saw closed borders, widespread job losses, and GDP contract from $505 billion (Dec 2019) to $468 billion (June 2020)—a recession. The RBA responded by slashing the cash rate to a record low of 0.10% in November 2020, holding it until May 2022. This aggressive move helped Australia quickly return to its pre-COVID GDP trajectory by December 2021, and asset prices surged under the influence of ultra-loose policy.

Once lockdowns lifted, pent-up demand met constrained supply. Consumers, flush with savings, began spending into an economy unable to meet demand, fuelling inflation. Central banks initially dismissed this as “transitory”. However, as inflation fed into expectations and government spending remained elevated, prices rose rapidly.

The RBA eventually reversed course, initiating a tightening cycle to curb inflation, which peaked at 7.8% in December 2022—well above its 2–3% target. Critics argue that the delay in rate hikes gave inflation room to run. But another view is that monetary policy was simply overwhelmed: while central banks tightened, fiscal policy remained stimulatory, blunting the intended effects.

A New Conundrum

Today, we’re entering what looks like another contractionary phase. But with central banks and governments pursuing divergent agendas, monetary policy’s effectiveness is again in question. Australia now faces rising inflation and rising unemployment—an unusual pairing, as inflation typically falls during contractions.

This places the RBA in a difficult position: whichever lever it pulls, it risks failing at least one of its core mandates.

Long End Collapse

This uncertainty is reverberating through bond markets. The yield curve is steepening at the long end—30-year bonds are pricing in higher long-term rates even as short-term policy rates are being cut. This inversion suggests deep investor scepticism about economic stability and long-term debt sustainability.

|

|

1 year

|

30 year

|

|

UK

|

3.861

|

5.606

|

|

Australia

|

3.489

|

5.173

|

|

US

|

3.774

|

4.9

|

|

Japan

|

0.705

|

3.286

|

|

France

|

2.0007

|

4.453

|

|

Canada

|

2.606

|

3.841

|

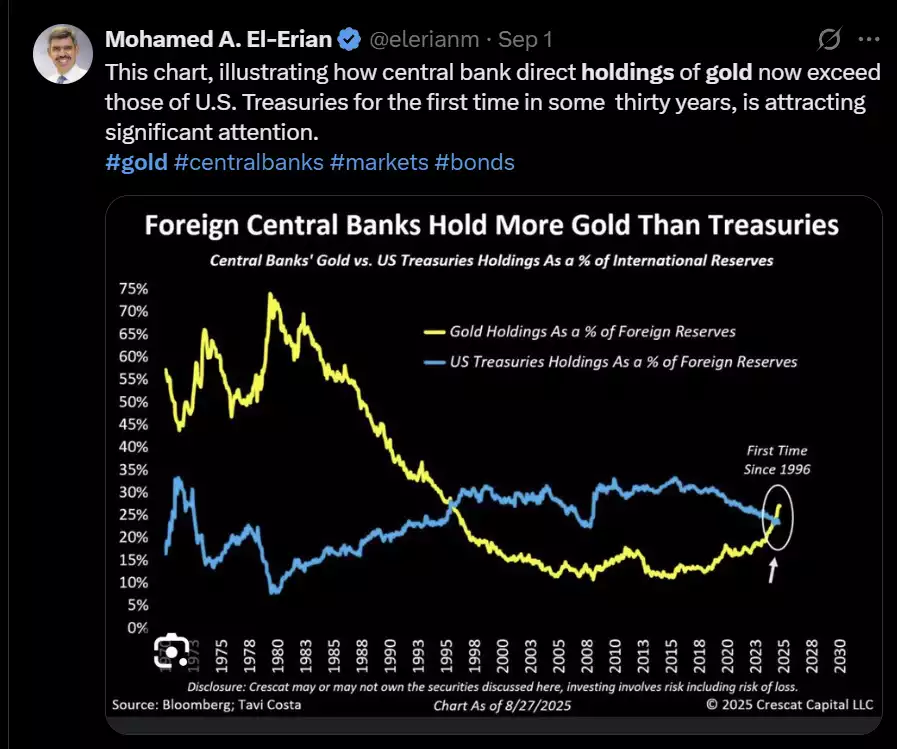

Meanwhile, gold has surged 6% this week—a sharp move. Over the past 12 months, even central banks have been reducing their bond holdings and increasing their gold reserves. For the first time since 1996, global central bank gold holdings now exceed their US Treasury holdings.

If even governments are losing faith in each other’s ability to manage debt, perhaps we are witnessing the failure of 90 years of active monetary policy. The assumptions underpinning Keynes’ framework—namely, that central banks can effectively guide economies using interest rates alone—are now under serious pressure.