Here We Go Again: UBS Making Same Mistakes as Credit Suisse

News

|

Posted 20/09/2023

|

2626

As you are probably aware (because we reported it here), about six months ago, investors suffered heavy losses when UBS orchestrated the bailout of the now-defunct Swiss banking giant Credit Suisse.

This move essentially flipped the traditional recovery hierarchy, protecting equity value at the expense of AT1 bondholders, thus avoiding the appearance of a bank failure. Astonishingly UBS is currently testing the waters to see if history can repeat itself, as reported by the Financial Times.

They are engaging potential investors in a roadshow for an AT1 (Contingent Convertible) bond of their own, despite the infamous write-down of similar bonds issued by their fellow Swiss bank, which shattered market confidence and triggered a wave of legal action. It seems that market confidence wasn't crushed quite enough, and UBS is now gauging the appetite for such bonds among investors.

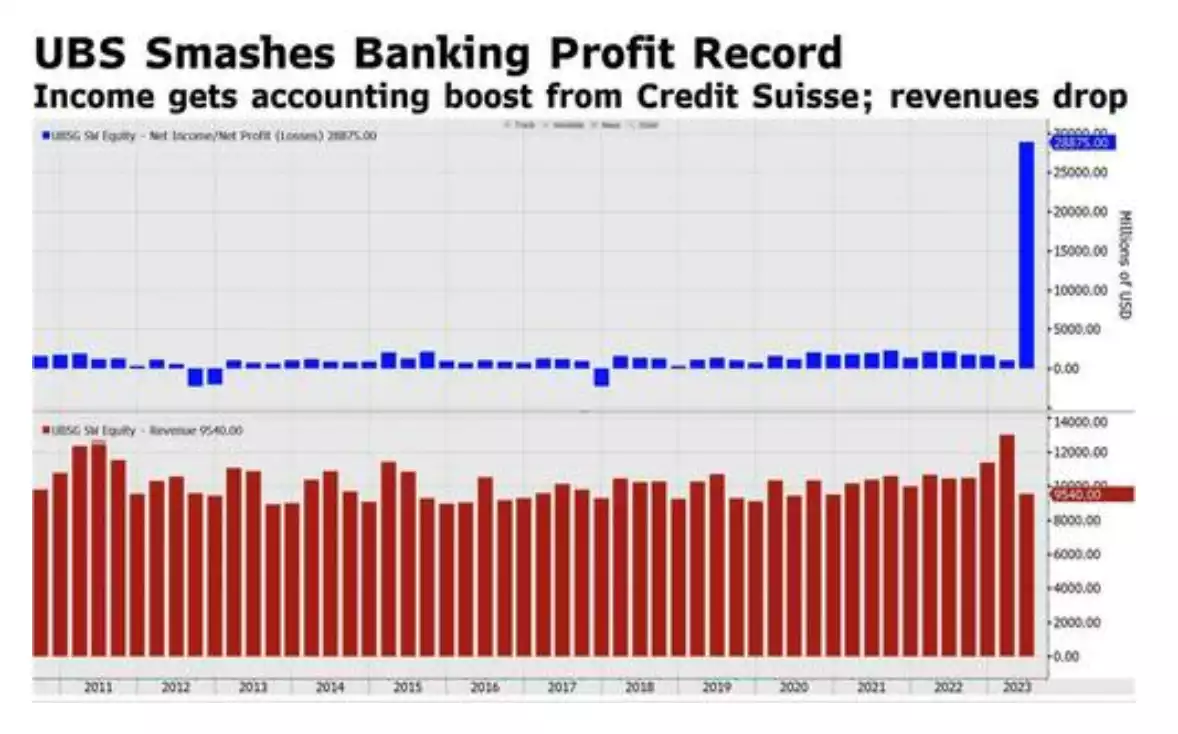

According to reports, UBS executives are making their pitch to investors following robust quarterly results, which saw the bank achieve an outstanding $29 billion in earnings – the highest ever quarterly profit reported by any bank. This exceptional performance was partly attributed to the strategic transfer of "good" Credit Suisse assets to UBS, while Swiss taxpayers remained responsible for the "bad" ones. This might sound very familiar to the JP Morgan windfall on the fall of First Republic Bank in the US, reportedly making $26b whilst the US tax payer lost $13b as we discussed here.

During the roadshow, while UBS proposed alterations to the terms of future additional tier 1 securities to make them more appealing to bondholders, the underlying security still carries significant risk in a worst-case scenario.

UBS is under pressure to replace up to $17 billion worth of Credit Suisse AT1 bonds in the coming years to enhance the efficiency of the bank's capital structure, freeing up funds for shareholder returns and potential acquisitions.

Nevertheless, not all investors are easily swayed, as the memory of bondholders losing billions during the Credit Suisse rescue, where regulatory changes favoured shareholders over AT1 holders, lingers in their minds.

This move disrupted the traditional hierarchy of bank creditors and undermined confidence in AT1 bonds, which were introduced after the GFC to reduce risk to depositors and impose stricter capital requirements on banks in the event of failure.

“UBS are working frantically in the background to sort this out,” said a bond fund manager who recently met the bank’s representatives. “They need to give investors confidence that the capital structure won’t be inverted and the rules won’t be changed at the eleventh hour again.”

One potential solution discussed is replacing UBS's AT1 bonds, designed for write-downs in troubled times, with versions that would convert into equity. While this approach may be more attractive to investors, it doesn't eliminate the inherent risks.

“Equity conversion is probably better and there is more demand if you do it like that,” said another bond investor. “But we are not naive and don’t think it changes the risk.”

AT1 bonds have no maturity date but can typically be called by the issuer every five years. Banks often exercise this option and issue replacements. UBS currently has a $510 million bond callable at the end of November and a $2.5 billion bond callable at the end of January.

When UBS in August reported $29bn in profit, a record quarterly figure for a bank, due to an accounting gain from the Credit Suisse takeover, chief executive Sergio Ermotti said it was weighing up when to re-enter the AT1 market.

“We are watching the market carefully,” he said. “We will assess the timing and the need of tapping the markets when appropriate.”

“They will have to make their bonds as investor-friendly as possible,” said a bond manager involved in the UBS roadshow. “They will have to pay a premium, too.”

“I think they’ll be able to get a deal done,” said another investor. “UBS is obviously an absolutely massive bank now, probably too big to fail and too big to save for the Swiss economy now, considering its size.”

Though clearly some investors believe that given UBS's colossal size, it is too big to fail, remember similar things were said about Credit Suisse less than a year ago.

The downside of this UBS optimism may lead to a rush of investors eager to get a piece of the action, ignoring the warning signs in the fine print. In a few years, they may find themselves suing UBS for massive write-downs, just as the fine print cautioned.

Unlike before, Switzerland, having agreed to UBS becoming a bank larger than its GDP, may not be able to bail anyone out, and both UBS and the Swiss economy could face dire consequences.