Government Deficits and Growing Wealth Inequality

News

|

Posted 27/11/2025

|

1061

When governments run persistent deficits, the results are rarely what’s promised. More often than not, wealth becomes more concentrated among those who own assets, while those living off wages alone struggle to keep up with rising costs.

If you've had the capacity to invest in shares, property, gold, or crypto over the past two decades, chances are your wealth has grown. But if your income comes primarily from wages, you’ve likely felt the pinch—from rising mortgage repayments to higher everyday costs. Yes, tax rates may have fallen and government benefits may have increased, but these supports are often eroded by inflation, leaving many worse off in real terms.

Ironically, government spending intended to address wealth imbalances often exacerbates them. Running large deficits to fund transfers or short-term relief often fuels asset price inflation, disproportionately benefiting those already holding assets. When voters support such policies without understanding these dynamics, the cycle perpetuates—well-intentioned spending ends up widening the gap it aims to close.

A Shift in New York

New York, often seen as the financial capital of the world, is now pursuing policies that reflect a more interventionist approach—proposals like rent freezes, higher taxes on high earners, and even government-owned supermarkets. While these may appeal to struggling residents, history has shown that such measures often lead to unintended consequences: reduced investment, declining tax revenues, and capital flight.

One notable example is the rent control policies introduced in New York City during the 20th century. Initially aimed at providing affordable housing, these measures led to a long-term deterioration in the housing stock, disincentivised new development, and reduced property tax revenues. Many property owners chose to convert buildings or leave the market entirely, shrinking supply and ultimately exacerbating affordability issues.

High earners and businesses can and do relocate—many to lower-tax states like Florida—reducing the very revenue base needed to fund these policies. Rent controls, while offering temporary relief, can stifle new development, reduce housing supply, and ultimately worsen affordability over time.

Japan’s Latest Stimulus Sparks Bond Market Jitters

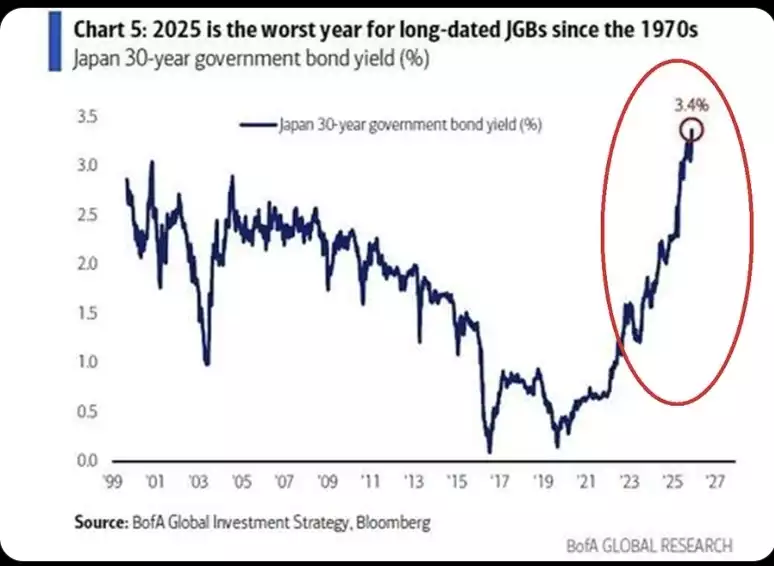

Japan is another example of a government turning to large-scale stimulus in an already indebted environment. The newly approved ¥21 trillion (US$135 billion) stimulus package has pushed the Yen to decade lows, while bond yields have surged to 30-year highs—reflecting growing investor concern.

This raises uncomfortable questions about the long-term solvency of governments and banks alike. A 30-year government bond bought today in Japan could lose half its value in real terms over the next decade. Stimulus-fuelled inflation and rising borrowing costs are exposing the vulnerabilities of even the most stable economies.

Australia’s Widening Wealth Gap

Despite strong employment figures and improved wage growth—especially among lower-income workers—Australia's wealth inequality continues to increase. Between 2021 and 2023, while wage inequality fell and unemployment dropped to 4.3%, wealth became more concentrated. The top 20% of households now control 62% of the nation's wealth (up from 59% in 2021), while the bottom 10% hold just $6,200 in net assets.

The issue isn’t just about income; it's about asset ownership. Deficit-funded social spending, while politically popular, risks fuelling inflation—particularly in housing and financial markets—undermining the purchasing power of wages and savings.

Calls for higher taxes on the wealthy as a solution are becoming less effective. A shrinking tax base, coupled with growing reliance on government support, places more pressure on a smaller group of taxpayers. This trend is unsustainable.

A Call for Fiscal Discipline

Rather than relying on continuous stimulus and expanding benefits, Australia may benefit from mechanisms like Switzerland’s “debt brake,” which enforces fiscal discipline by limiting how much governments can spend relative to revenues.

Until such reforms are in place, individuals must take responsibility for their own financial resilience. In a world of asset inflation and currency debasement, owning hard assets like gold and silver may be one of the few reliable ways to protect purchasing power over the long term.