Gold & China’s Belt and Road Initiative – MUST READ

News

|

Posted 29/01/2019

|

9592

Today we look at the flipside of the Chinese debt mountain and how it differs to the US’s debt mountain. We delve deeper into the biggest strategic trade and infrastructure initiative in the world today, the Belt and Road Initiative. This is much more than trade and infrastructure, it is about power and gold is a key element in this play. For a broader appreciation of how gold may yet again inevitably regain monetary ascendancy in our world, we put today’s article in the must read category.

Again we see a clear divergence between the ‘East’ and the ‘West’.

Recently we wrote of the very worrying amount of debt China holds and the slowdown of their economy. The flipside for some is that, whilst yes they have accumulated the world’s biggest debt pile, they have done so building real things like infrastructure and housing and whilst the growth is slowing, it is still at a rate double the rest of the western world. What is important for this argument is that they have also been investing very heavily in gold. The thesis is that once the inevitable day of reckoning occurs (as it always does with such a debt load) they will have real assets. More importantly, if that day of reckoning sees a collapse of the USD (of which we wrote last week some Governments appear to be preparing for) they and their strategic partners have an asset whose value can be inflated and underpin a new global reserve currency. Gold.

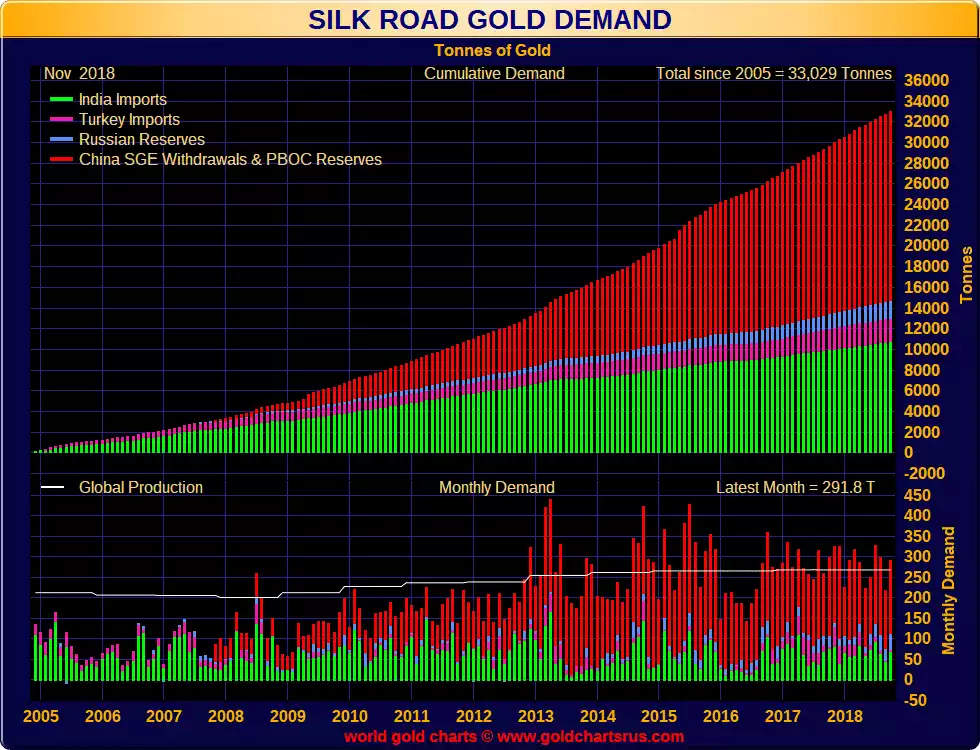

No doubt the most prominent investment and strategic play China is currently undertaking is the Belt and Road Initiative (the modern Silk Road). This $1 trillion initiative is as much about power and global strategy as it is about infrastructure and trade. The article below, courtesy of London’s The Guardian is a must read look at arguably the biggest strategic infrastructure project in the world today. But first, we want you to read this article with the following chart firmly in your mind. It is a chart mapping the simply epic accumulation of gold by the key nations of the Belt and Road Initiative. What the chart displays is that since 2005, and with gusto since the GFC, this handful of eastern countries have accumulated more gold than mine production. Keep in mind too that it excludes the widely believed massive accumulation of gold by the Chinese government beyond that disclosed.

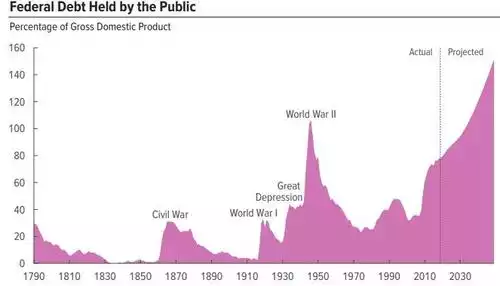

Additionally, for context let’s look at the very latest debt projections from the US government’s Congressional Budget Office. That chart shows the US Government adding $1 trillion of debt per year. That’s the same as the reported total Chinese investment into the Belt and Road Initiative.

From The Guardian’s Lily Kuo and Niko Kommenda….

“What is China's Belt and Road Initiative?

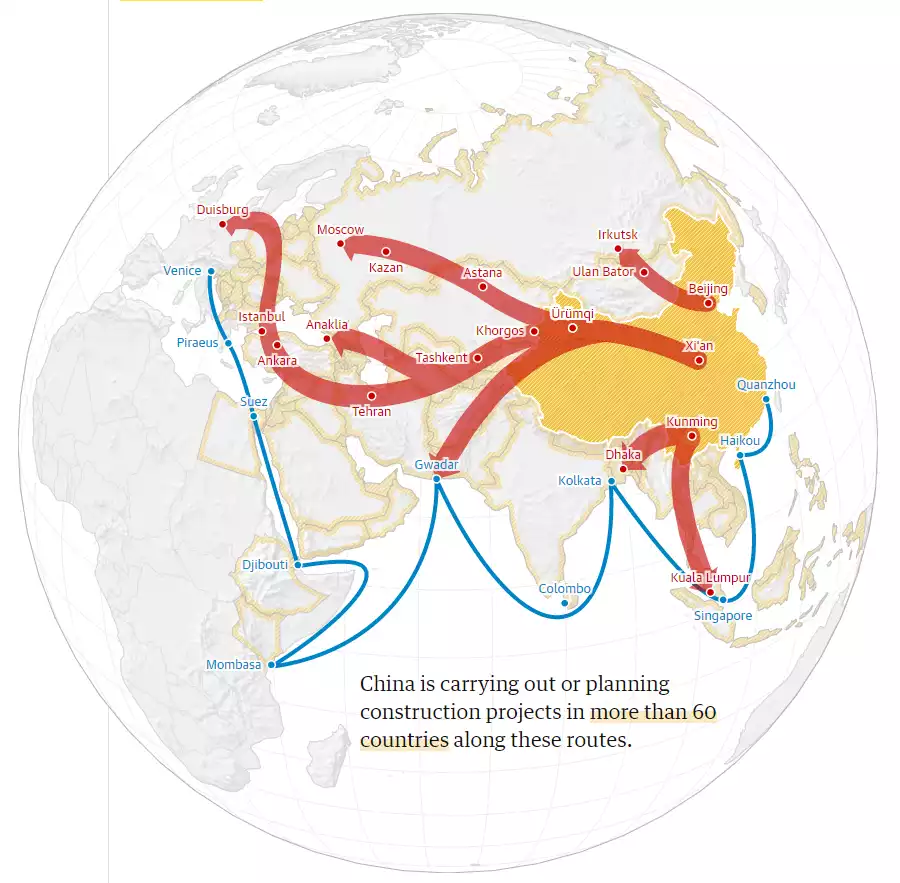

The project is often described as a 21st century silk road, made up of a “belt” of overland corridors and a maritime “road” of shipping lanes.

Beijing’s multibillion dollar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been called a Chinese Marshall Plan, a state-backed campaign for global dominance, a stimulus package for a slowing economy, and a massive marketing campaign for something that was already happening – Chinese investment around the world.

Over the five years since President Xi Jinping announced his grand plan to connect Asia, Africa and Europe, the initiative has morphed into a broad catchphrase to describe almost all aspects of Chinese engagement abroad.

Belt and Road, or yi dai yi lu, is a “21st century silk road,” confusingly made up of a “belt” of overland corridors and a maritime “road” of shipping lanes.

From South-east Asia to Eastern Europe and Africa, Belt and Road includes 71 countries that account for half the world’s population and a quarter of global GDP.

Everything from a Trump-affiliated theme park in Indonesia to a jazz camp in Chongqing have been branded Belt and Road. Countries from Panama to Madagascar, South Africa to New Zealand, have officially pledged support.

How much money is being spent?

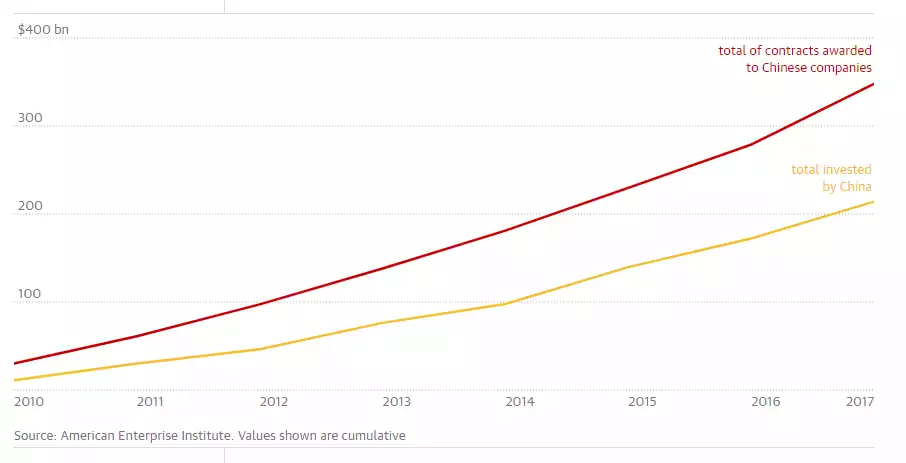

The Belt and Road Initiative is expected to cost more than $1tn (£760bn), although there are differing estimates as to how much money has been spent to date. According to one analysis, China has invested more than $210bn, the majority in Asia.

But China’s efforts abroad don’t stop there. Belt and Road also means that Chinese firms are engaging in construction work across the globe on an unparalleled scale.

To date, Chinese companies have secured more than $340bn in construction contracts along the Belt and Road.

However, China’s dominance in the construction sector comes at the expense of local contractors in partner countries.

The vast sums raked in by Chinese firms are at odds with the official rhetoric that Belt and Road is open to global participation and suggest that the initiative is also motivated by factors other than trade, such as China’s need to combat excess capacity at home.

What are the risks for countries involved?

More recently, governments from Malaysia to Pakistan are starting to rethink the costs of these projects. Sri Lanka, where the government leased a port to a Chinese company for 99 years after struggling to make repayments, is a cautionary tale.

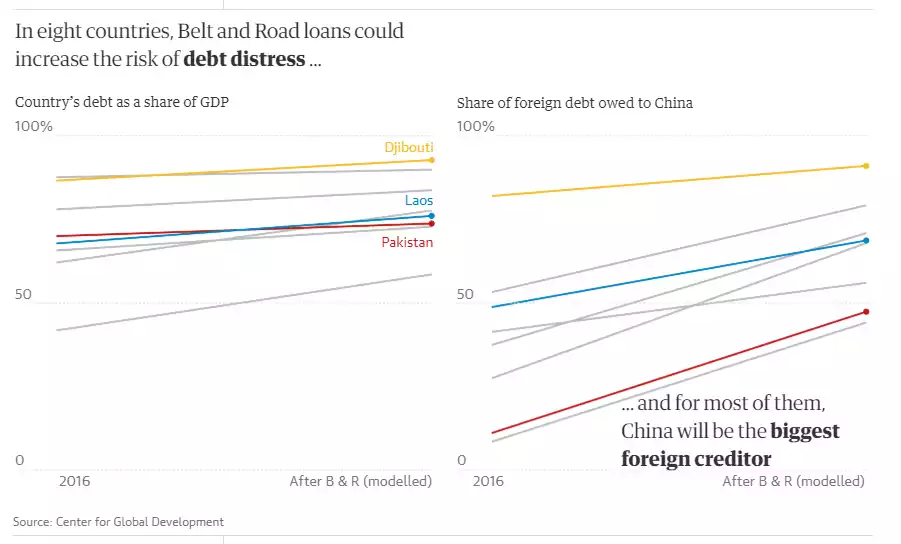

Earlier this year, the Center for Global Development found eight more Belt and Road countries at serious risk of not being able to repay their loans.

The affected nations – Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, the Maldives, Mongolia, Montenegro, Pakistan and Tajikistan – are among the poorest in their respective regions and will owe more than half of all their foreign debt to China.

Critics worry China could use “debt-trap diplomacy” to extract strategic concessions – such as over territorial disputes in the South China Sea or silence on human rights violations. In 2011, China wrote off an undisclosed debt owed by Tajikistan in exchange for 1,158 sq km (447 sq miles) of disputed territory.

“There are some extreme cases where China lends into very high risk environments, and it would seem that the motivation is something different. In these situations the leverage China has as lender is used for purposes unrelated to the original loan,” said Scott Morris, one of the authors of the Washington Centre for Global Development report.

Why is the initiative sparking global concern?

As Belt and Road expands in scope so do concerns it is a form of economic imperialism that gives China too much leverage over other countries, often those that are smaller and poorer.

Jane Golley, an associate professor at Australian National University, describes it as an attempt to win friends and influence people. “They’ve presented this very grand initiative which has frightened people,” says Golley. “Rather than using their economic power to make friends, they’ve drummed up more fear that it will be about influence.”

According to Shan Wenhua, a professor at Jiaotong University in Xi’an, Xi’s signature foreign policy is “the first major attempt by the Chinese government to take a proactive approach toward international cooperation … to take responsibility.”

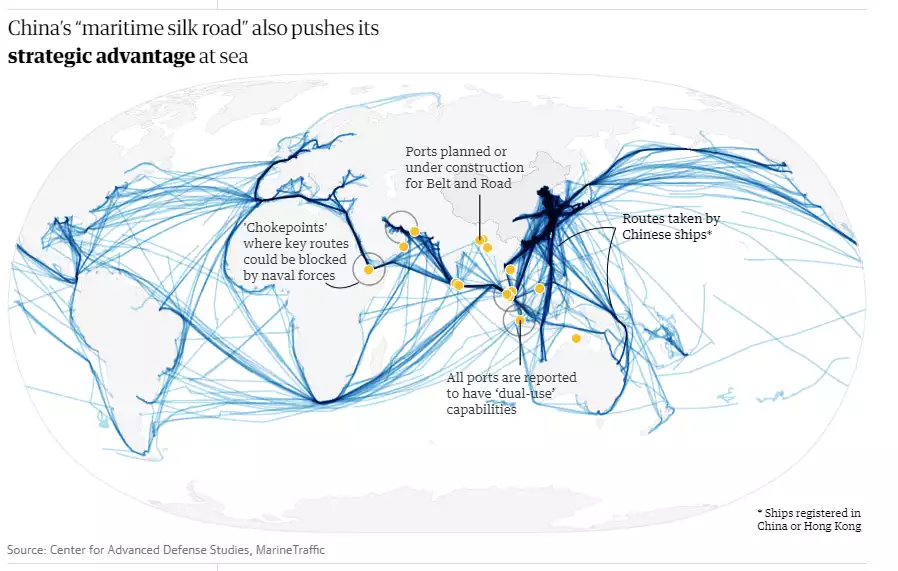

Some worry expanded Chinese commercial presence around the world will eventually lead to expanded military presence. Last year, China established its first overseas military base in Djibouti. Analysts say almost all the ports and other transport infrastructure being built can be dual-use for commercial and military purposes.

“If it can carry goods, it can carry troops,” says Jonathan Hillman, director of the Reconnecting Asia project at CSIS.

Others worry China will export its political model. Herbert Wiesner, general secretary of Germany’s PEN Center, says human rights are being “left in the ditches by the sides of the New Silk Road”.

Where does it end?

Belt and Road is likely to continue, not least because these projects signal loyalty to Xi. The initiative has been enshrined in the Chinese communist party’s constitution, which also eliminated term limits, leaving Xi room to continue Belt and Road for as long as he wants.

It also gives disparate Chinese projects overseas the veneer of being part of a grand strategic plan, according to Winslow Robertson, a specialist in China-Africa relations. It is not a centralised initiative, so much as a brand, he says.

“Who determines what is a Belt and Road project or a Belt and Road country? Nobody is sure. Everything and nothing is Belt and Road.”

What’s next?

Not all of the most ambitious Belt and Road projects are about hard infrastructure. China plans to set up international courts, in Shenzhen and Xi’an, the former hub of the original Silk Road, to resolve commercial disputes related to Belt and Road.

“It’s a reminder BRI is about more than roads, railways, and other hard infrastructure,” said Jonathan Hillman, director of the Reconnecting Asia project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “It’s also a vehicle for China to write new rules, establish institutions that reflect Chinese interests, and reshape ‘soft’ infrastructure.”

Officials have said the courts, to be based on the judiciary, arbitration and mediation agencies of China’s Supreme People’s Court in Beijing, will follow international rules and will invite legal experts from outside China to participate.

Legal experts say the courts will likely be modelled on the Dubai International Financial Centre Courts and the International Commercial Court in Singapore, which has already struck an agreement with China to resolve Belt and Road-related disputes.

But critics of the independence of the country’s judicial system, which traditionally answers to China’s ruling communist party, worry the courts will favour Chinese parties over foreign firms.”