Central Banks Repatriating

News

|

Posted 18/03/2025

|

3583

Concerns over geopolitical tensions, asset security, and a desire to reduce reliance on foreign custodians in the U.S. and UK, are the drivers behind global central banks moving to repatriate their bullion reserves back to domestic soil.

Central banks hold approximately 17-20% of all gold ever mined, with the World Gold Council estimating global reserves to be at over 36,700 tons as of late 2023. Much of the world’s gold has historically been stored significant portions of their gold reserves abroad, primarily the New York Federal Reserve Bank and the Bank of England. This practice originated in the post-World War II era and Bretton Woods, when the U.S. emerged as the dominant economic power and held most of the world’s gold reserves. Storing gold abroad offered logistical convenience, security during periods of instability, and facilitated international trade and transactions easily.

The landscape has shifted dramatically in past years. Unending geopolitical tensions, and high-profile sanctions—most notably those imposed on Russia following its 2014 annexation of Crimea and the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, have prompted central banks to reassess the risks of storing gold overseas. The freezing of nearly half of Russia’s US$640 billion in gold and foreign exchange reserves by Western nations underscored the vulnerability of assets held abroad. This event, coupled with other examples like the seizure of Venezuela’s gold by the Bank of England, has fuelled a global push toward repatriation. Additionally, central banks are increasingly viewing gold as a critical component of national sovereignty and economic resilience. The WGC’s mid-2024 survey found that 81% of central bankers expect global gold reserves to rise over the next year, with 42% citing its role as a long-term store of value and its classification as a tier 1 asset as reasons. This sentiment, combined with a decline in confidence in the U.S. dollar-dominated financial system, has accelerated both gold purchases and repatriation efforts.

Several central banks have made headlines in past years for repatriating their gold reserves.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) repatriated 100 tons of gold from vaults in the UK, bringing it back to India in May 2024. They reduced the proportion of its gold held abroad from 413.8 tons (as of late 2023) to approximately 313.8 tons. India’s total gold reserves stood at 822.1 tons by early 2024, making it the eighth-largest holder globally. It reflected India’s growing emphasis on domestic control over its assets amid geopolitical uncertainty namely the Russia-Ukraine conflict and rising storage costs abroad. India’s broader strategy is clearly increasing gold reserves, with the RBI adding 37 tons in net purchases year-to-date by mid-2024.

Deutsche Bundesbank in Germany began repatriating its gold in 2012 following public and political pressure, particularly after the German Federal Court of Auditors criticized the Bundesbank’s auditing of foreign-held reserves. By 2016, over 583 MT had been transferred back to Frankfurt from New York and Paris. Currently, nearly half of Germany’s 3,351.53 MT of gold is stored domestically, with the remainder in New York (over a third), London (about an eighth), and a small amount in Paris. The repatriation was initiated by concerns over transparency and security, as well as a desire to bolster public confidence in Germany’s economic sovereignty. The process was completed ahead of schedule in 2017, signalling a long-term shift in policy.

In 2014, De Nederlandsche Bank in the Netherlands secretly repatriated 122 tons of gold from the New York Federal Reserve, worth approximately US$5 billion at the time. This reduced the share of its gold held in the U.S. to 31%, with 31% now stored in Amsterdam and the rest split between Ottawa and London. The move was driven again by public concerns about the safety of gold stored abroad in the wake of the eurozone debt crisis, and doubts about the integrity of foreign custodians like the Federal Reserve, which has not undergone a comprehensive audit since 1953.

In 2019, Poland’s National Bank of Poland (NBP) completed the repatriation of 100 tons of gold from the Bank of England. The NBP has also been a significant buyer, adding 19 tons in Q2 2024 alone, bringing its total reserves to 377 tons (13% of total reserves). Governor Adam Glapinski has expressed a goal of increasing gold’s share to 20%. Poland’s repatriation and purchasing reflect a strategic effort to enhance financial security amid regional tensions, particularly with Russia, and to diversify away from dollar-based assets.

In other cases, Eastern European nations like Serbia, Hungary, and Slovakia have also repatriated gold in recent years, citing risk in international custody being the main reason. Hungary, for instance, increased its gold reserves tenfold in 2018 and brought much of it home from the Bank of London. Turkey has been a net buyer (adding 159 tons in 2023 before resuming purchases), it has also emphasised domestic storage and actively reduced reliance on foreign vaults. Though not actively repatriating as most of their gold is domestically sourced, Russia and China have significantly increased their reserves - Russia has increased its reserves to over 2,300 tons, and China to 2,262 tons by mid-2024.

Who owns the gold the banks are bringing back? The gold being repatriated belongs to the respective bank of each nation, which manage these reserves on behalf of their governments and citizens. Central banks like the RBI, Bundesbank, DNB, and NBP are public institutions tasked with safeguarding national wealth and ensuring monetary stability. The gold they hold is typically classified as part of a country’s official reserves, alongside foreign currencies and other assets.

However, complications arise when gold is stored abroad. When a central bank deposits gold with a foreign custodian (e.g., the New York Fed or Bank of England), it retains legal ownership, but the physical custody and potential use of that gold can become unclear.

The custodian does not own the gold but is responsible for its safekeeping. Historically, custodians like the Federal Reserve have been accused of rehypothecating their bullion stores. The Russia and Venezuela cases highlight that foreign-held gold can be frozen or seized under international sanctions, raising questions about effective control despite legal ownership. Gold stored abroad is often held in allocated storage, but if it were unallocated, ownership could theoretically be contested in a crisis. In practice, repatriation ensures that legal ownership aligns with physical possession, eliminating these risks. The gold repatriated by India, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, and others remains unequivocally theirs, stored in national vaults under their control.

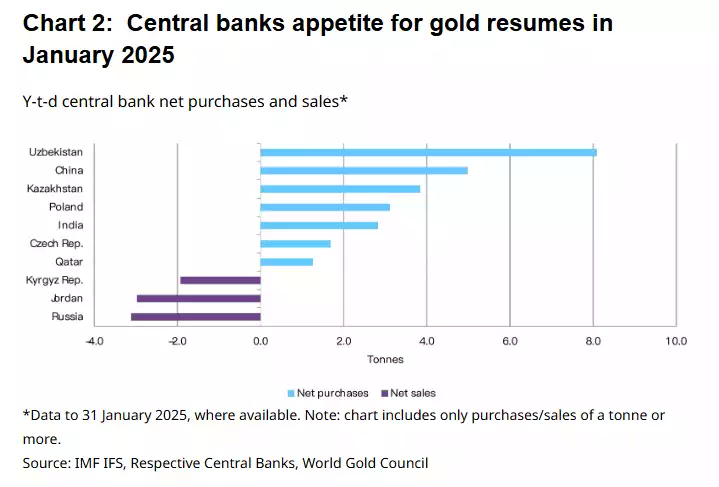

The repatriation trend signals a broader shift in the global financial order. Central banks are not only bringing gold back onto domestic soil, but are also increasing purchases—net buying exceeded 1,000 tons annually in 2022 and 2023, with emerging markets like India, Poland, and Uzbekistan heading these purchases. This reflects a move “from West to East,” as Asia and Eastern Europe assert greater influence over the gold market, while Western vaults like the Bank of England are seeing massive outflows – a 465-ton drop in custody holdings over three years, despite global reserves growing by 1,160 tons. U.S.-led sanctions and other geopolitical tensions have eroded trust in Western financial systems, prompting nations to prioritise self-custody. The U.S. remains the largest gold holder (8,133.46 MT) - much of it stored at Fort Knox, Denver, and West Point.

The gold repatriation by central banks like those of India, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, and Nigeria reflects a total, global re-evaluation of economic security and sovereignty. As geopolitical uneasiness persists and confidence in fiat currencies is disappearing, gold’s role as a trusted asset continues to grow, driving both its repatriation and accumulation. Physical possession of gold has become just as critical as its ownership.

Watch the Ainslie Insights video discussion of this article here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RIHgj8iUHYE