Australian Rental Crisis only to get worse, GDP dies, and the RBA is struggling for a solution.

News

|

Posted 02/03/2023

|

10580

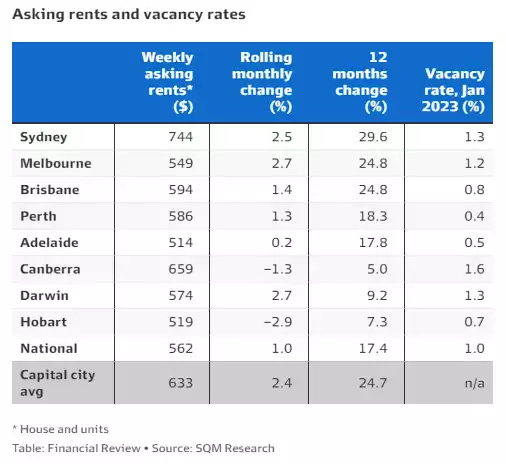

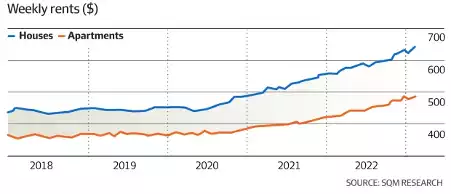

Australian rents in capital cities increased by nearly 25% in 2022, contributing to a once in a generation cost of living crisis that is only being exacerbated by the recent interest rate rises.

Earlier in the week, we broke down the extraordinary Cost Of Living Crisis Australians are currently facing. Today we will take a specific focus on one of its main components, the chaotic Australian rental market.

The surge in Australian rental prices has been one of the largest national talking points to start the year, and has received a particular focus when the Chinese government announced that they had banned online study at foreign universities, forcing hundreds of thousands of Chinese students to return overseas including up to 40,000 to Australia.

As a direct consequence of this surprise policy, asking rents in capital cities jumped a record breaking 2.4% in the past 30 days alone.

In saying this however, these problems remain at least somewhat systematic, and go beyond this once off exorbitant increase in international student migration, as over the past year we have seen a 24.7% increase in rental prices in capital cities.

Additionally, enquiries per rental listing is up more than a third, while capital city rental listings are down 26.3%, the lowest since 2003.

Louis Christopher, SQM Research managing director, puts the current state of the rental marketplace into greater perspective.

“This is the fastest rate of growth in rents recorded on our index,” Christopher said.

“There was a period of tightness in the rental market in the early 2000s that lasted about a year, but the rate of increase wasn’t at this level.”

Christopher went on to say that the sharp rise in rents would feed into inflation measures used by the ABS.

“The current asking rents will ultimately flow in the ABS series, but there is a lag of about 18 months, which means that the rent currently being reflected on the inflation data was from early 2021. So, these recent numbers will only be factored in later this year through to next year which will contribute to the property side of inflation.”

The fact that that the rental prices aren’t being represented in the current inflation data is worrying to say the least. Particularly because rental prices have an outsized impact on the CPI (though most would argue it should have an even greater impact).

“Rents represent just under 6 per cent of the CPI basket, but it’s the single largest component of the CPI basket, so it’s a fairly significant contributor,” Christopher said.

The RBA is in a very difficult position, as any further increases in cash rates will only discourage property investment and private infrastructure spending, further tightening the rental supply, and by extension putting additional upward pressure on rental prices.

“If the cash rate rises above 4 per cent, it is likely home buyers, including investors, will largely stay away from the housing market for another year, and so investment dwelling approvals will remain doldrums, setting us up for a major shortage in later 2024 and 2025,” Christopher said.

“The RBA is in a difficult position right now. And it’s becoming increasingly improbable that the RBA will manage a soft landing.”

The RBA meet this coming Tuesday and will almost certainly increase rates for a 10th consecutive time. They will know this inflation boost is coming. When you consider the above with the insights provided by Alex Hutchinson in our recent Insights interviews here and here, particularly her Aussie mortgages warning in light of above, you have the makings of a very hard landing for Australia.

Yesterday we saw the Q4 national accounts released from the ABS and it was terrible for Aussie households. GDP per capita (recall all the immigration above and as Alex mentions) was dead flat in the last quarter, and off just 0.1% in Q3. It was a similar outcome for domestic final demand. From MacoBusiness:

“So basically, the per capita economy is already teetering on recession, with the aggregate economy saved only by strong population growth via mass immigration.

The driver of the economic slowdown is household consumption, which grew by only 0.3% in the December quarter, and actually fell by 0.2% in per capita terms.

Household consumption is the main driver of the Australian economy and where it goes the economy typically follows:

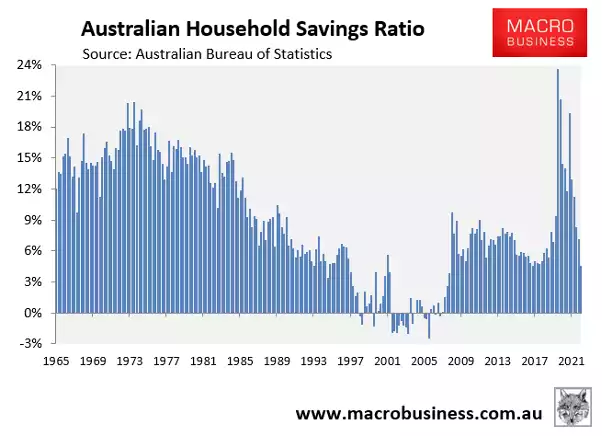

This slowing in household consumption came despite a sharp fall in the household savings rate to just 4.5% in the December quarter, down from 7.1% in the September quarter:

Basically, households are dipping into their savings to maintain consumption in the face of falling real wages, inflation, and increasing interest repayments following the RBA’s aggressive interest rate hikes.

Looking ahead, it is clear that household consumption and economic growth will fall further in 2023 as the RBA continues to tighten.

This, in turn, will result in a consumer-led per capita recession for Aussie households.”

In essence there is no easy way out for the RBA. That portends not just the increasing risk of a recession but highly volatile markets as it is sorted out.

Balance your wealth in an unbalanced world.

Submit your question to [email protected] and SUBSCRIBE to the YouTube Channel to be notified when the GSS Insights video is live.

**********************************************************************************